From Rulebook to Market Maker: The New Power of Regulation in the Indian Economy

In India’s current economic moment, regulation has moved decisively beyond its traditional role as a neutral framework for compliance. It now operates as a form of economic power, shaping market structure, influencing capital allocation, and determining competitive outcomes. Regulation no longer merely corrects market failures; it increasingly redistributes advantage.

This shift is not unique to India. Globally, regulatory expansion has been driven by financial instability, digitalization, climate risk, and national security concerns. However, in India, where markets are still deepening, institutional capacity varies, and enforcement discretion is high, the economic impact of regulatory power is unusually pronounced. The central insight is unmistakable: regulation today is not just about compliance; it has become a competitive differentiator.

Retrospective Interpretation, Regulatory Uncertainty

One of the most potent expressions of regulatory power lies in retrospective interpretation. While explicit retrospective legislation is relatively rare, the frequent issuance of interpretative circulars and “clarifications” often alters the meaning of existing rules after commercial decisions have already been taken.

Between 2014 and 2023, central regulators issued more than 9,000 notifications, circulars, and clarifications across taxation, financial regulation, corporate law, and environmental governance. A significant proportion of these were interpretative in nature, effectively changing compliance obligations without fresh legislative debate or parliamentary scrutiny.

The economic cost of this uncertainty is measurable. Parliamentary data indicates that over ₹8.5 lakh crore is currently locked in indirect tax disputes, much of it arising from classification and valuation ambiguities under GST. Average resolution timelines exceed five years, during which capital remains frozen, cash flows are impaired, and balance sheets weaken.

The telecom sector’s adjusted gross revenue (AGR) reinterpretation remains the most striking illustration. A regulatory redefinition transformed long-settled license assumptions into liabilities exceeding ₹1.4 lakh crore, fundamentally reshaping the sector’s competitive landscape. Beyond its immediate impact, the episode sent a broader signal across industries: regulatory interpretation can override commercial finality, even years later.

Compliance Costs or Barriers?

India’s regulatory architecture has grown denser over time, but not necessarily clearer. Multiple filings, overlapping reporting requirements, and sector-specific compliance regimes now define the operating environment for firms.

World Bank Enterprise Survey data indicate that Indian firms allocate a higher proportion of senior management time to regulatory compliance than their peers in East Asia. Crucially, this burden is not evenly distributed. MSMEs report compliance costs amounting to 5–7% of annual turnover, compared to under 2% for large firms with scale, in-house legal teams, and compliance infrastructure.

This asymmetry has structural consequences. High fixed compliance costs function as de facto barriers to entry, discouraging new entrants and penalising smaller firms. Regulation, in effect, indirectly shapes market concentration, not through explicit policy intent, but through friction that favors incumbency and scale.

Discretionary Enforcement and Selectivity

The most consequential dimension of regulatory power often lies not in the rulebook itself, but in how rules are enforced. Regulations may be universal in text, yet selective in application.

CAG observations and parliamentary committee reports have repeatedly flagged inconsistent enforcement practices and weak accountability mechanisms across regulatory institutions. From environmental clearances to financial market supervision, enforcement intensity varies widely across sectors and entities.

For firms, this converts legal risk into relational risk. Compliance becomes necessary but insufficient; outcomes increasingly depend on regulatory interpretation, enforcement posture, and perceived alignment with broader policy priorities. Regulation thus evolves from oversight into an instrument of market selection.

Approval Velocity as an Economic Signal

The speed, or lack thereof, of regulatory approvals has emerged as a silent but decisive determinant of competitiveness. Delays translate directly into cost overruns, lost market opportunities, and diminished internal rates of return.

Official project-monitoring data shows that stalled infrastructure projects routinely experience cost overruns of 20–25%, largely due to clearance and approval delays. At the same time, large infrastructure and defence projects routed through fast-track mechanisms now receive approvals within 9–12 months.

In contrast, sectors such as mining, environment-sensitive manufacturing, fintech, and digital platforms often face approval timelines extending 24–36 months, driven by layered central and state-level permissions. Capital flows respond predictably: investment gravitates toward sectors where regulatory timelines are compressed, and outcomes are more predictable.

Financial Regulation and Capital Allocation

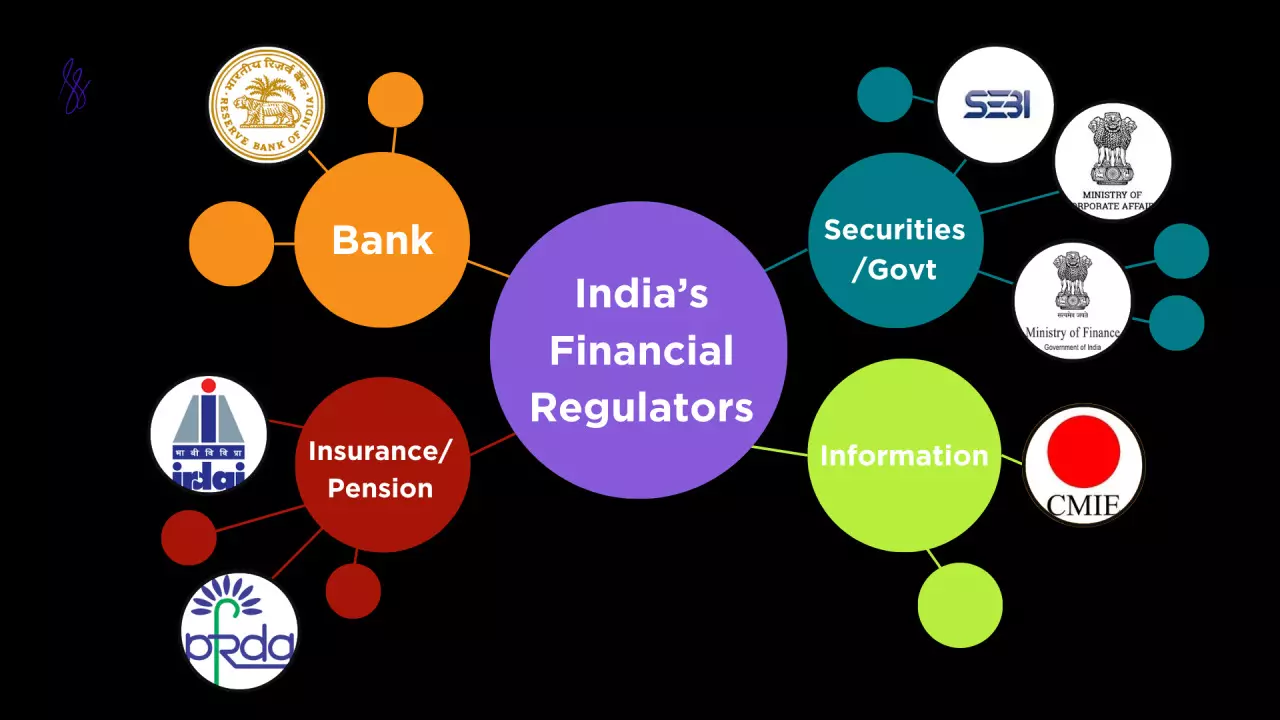

India’s financial regulators, most notably the RBI and SEBI, exercise direct and immediate influence over capital allocation through circulars, supervisory actions, and enforcement decisions.

RBI annual reports show that enforcement penalties on regulated entities increased more than fourfold between FY18 and FY23. Notably, many of these actions were grounded in supervisory assessments rather than explicit rule violations, expanding the scope of regulatory discretion.

The post-2018 NBFC liquidity crisis illustrates the systemic impact of such interventions. Following regulatory tightening, NBFC credit growth decelerated sharply, disproportionately affecting MSMEs and retail borrowers dependent on non-bank finance. Entire business models, particularly in fintech, now rise or fall on regulatory comfort rather than purely on risk pricing or innovation.

Judicial Oversight: A Weak Counterweight

In theory, judicial review serves as a counterweight to regulatory overreach. In practice, timing undermines its effectiveness.

Government submissions indicate that over 5,000 economic and regulatory cases are pending across higher courts, with average disposal timelines exceeding four years. Interim relief is limited, forcing firms to comply first and litigate later, often after business models have already been disrupted or rendered unviable.

As a result, regulatory decisions acquire de facto finality long before judicial scrutiny occurs, weakening the deterrent effect of legal oversight.

Governance Signals and Investor Perception

Global governance indicators consistently link regulatory predictability with investment and growth outcomes. Investors price regulatory risk explicitly into their decisions.

World Bank governance metrics and investor surveys repeatedly identify procedural opacity and enforcement inconsistency as material risk factors in India. CAG reports and parliamentary reviews reinforce these concerns. They are not abstract governance deficiencies; they translate directly into higher costs of capital, cautious investment behaviour, and constrained risk appetite.

When Regulation Becomes Market Power

The cumulative effect of these dynamics is clear. Regulation in India now functions as an economic sorting mechanism. Firms that can absorb compliance shocks, anticipate regulatory direction, and navigate discretionary enforcement gain a structural advantage. Others, even if more efficient, innovative, or consumer-focused, struggle to scale.

This is not an argument against regulation. Strong regulation is essential for financial stability, consumer protection, and environmental sustainability. But when regulatory power expands without corresponding transparency, predictability, and accountability, it begins to operate less as oversight and more as economic control.

India’s growth challenge, therefore, is not deregulation but better regulation: rules that are clear ex ante, enforcement that is consistent, discretion that is bounded, and time-bound approvals.

In today’s economy, regulation does not merely govern markets; it increasingly determines them.

(CA Abhinav Agarwal is a qualified Chartered Accountant and co-founder of INDIFINVEST.COM, the brand identity of AAAIP Finvest Services, one of the leading financial services firms.)