Metals, Markets, and the Fragility of Global Economic Faith

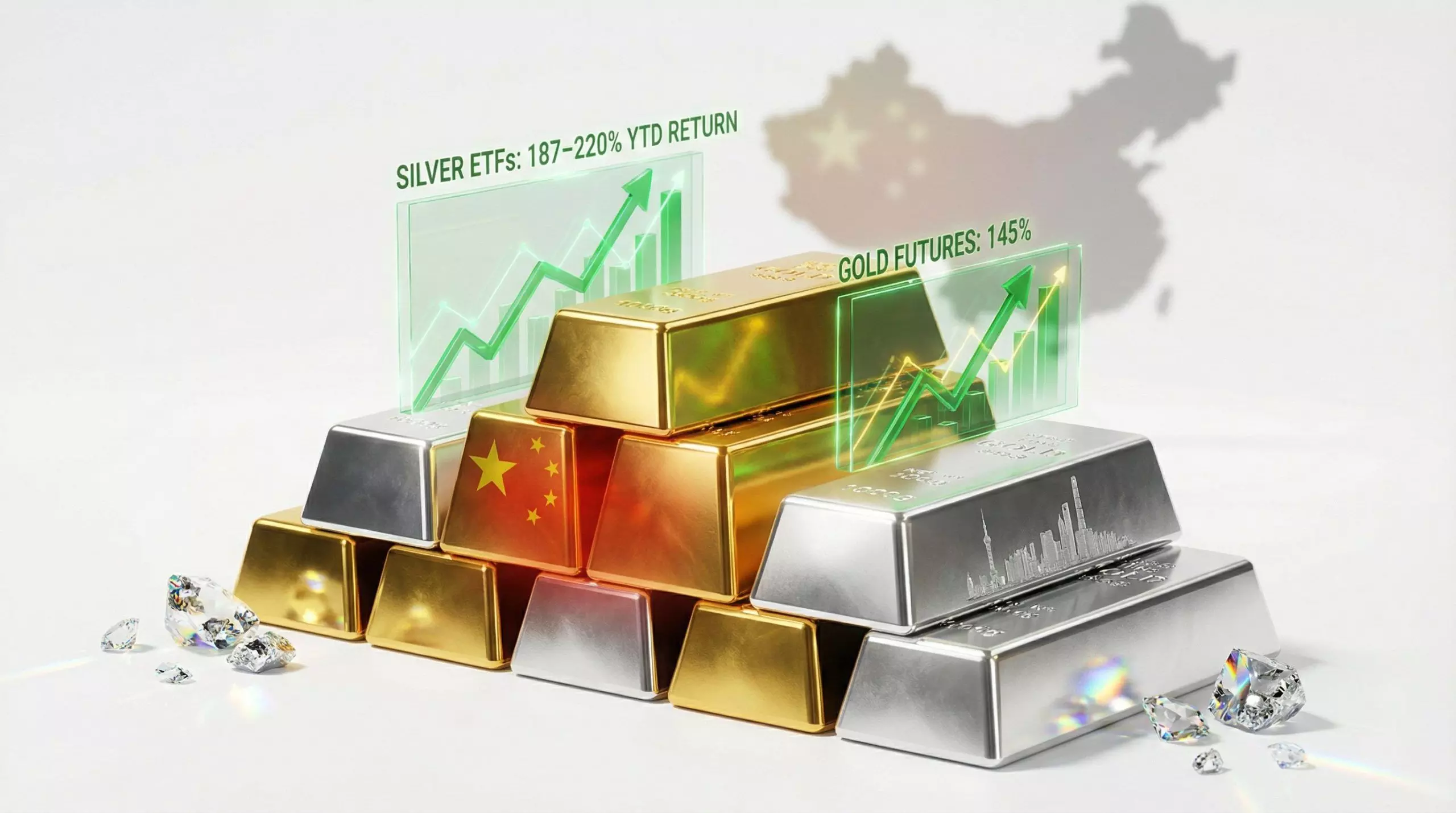

The recent surge in prices of platinum, palladium, and copper has startled investors and policymakers alike, raising fundamental questions about the sustainability of global markets and the credibility of governments in maintaining economic stability. Between early April and October 2025, platinum and palladium prices soared nearly 90%, outperforming even gold and silver, as investors sought refuge in assets that central banks cannot print or digitally create. Copper, traditionally seen as the bellwether of industrial demand, has climbed to its highest levels in three decades, reflecting both supply constraints and speculative flows. According to the International Energy Agency’s Global Critical Minerals Outlook 2025, price volatility and supply chain bottlenecks in critical minerals have become systemic, driven by geopolitical tensions, energy transition pressures, and concentrated production in a handful of countries.

The macroeconomic implications are stark. Platinum deficits are projected to persist through 2029, averaging 727,000 ounces annually, or nearly 9% of global demand. Palladium, though expected to move into surplus by 2026, remains vulnerable to shocks in automotive and electronics sectors. Copper’s rally is underpinned by electrification and renewable energy demand, with global consumption projected to rise 2.5% annually through 2030. Yet the supply side is constrained by declining ore grades, environmental restrictions, and geopolitical risks in producer nations such as Chile, Peru, and the Democratic Republic of Congo. This imbalance between demand and supply has created a speculative environment where investors hedge against inflation, fiscal deficits, and currency depreciation by pouring capital into metals, thereby amplifying price spikes.

The geopolitical backdrop exacerbates these dynamics. The ongoing Russia–Ukraine war has disrupted supplies of palladium and nickel, as Russia accounts for nearly 40% of global palladium exports. Sanctions and logistical bottlenecks have tightened availability, pushing prices upward. Simultaneously, tensions between the United States and Venezuela over oil and resource nationalism have undermined investor confidence in commodity markets. China, which dominates rare earth production with over 60% of global output, has leveraged its position to influence supply chains, while other countries remain dependent on Russia for critical inputs. This concentration of supply in politically volatile regions has created systemic risk, where any conflict or sanction reverberates across global markets.

The scientific and technological dimension is equally critical. Rare earth elements, platinum group metals, and copper are indispensable for clean energy technologies, electric vehicles, and advanced electronics. The International Energy Agency notes that demand for critical minerals could quadruple by 2040 under net zero scenarios IEA –. Yet investment in mining and refining has lagged, with capital expenditure in the sector declining by 25% since 2012. This underinvestment, coupled with rising extraction costs, has created structural deficits. Investors, aware of these constraints, have shifted portfolios toward metals, not only as hedges against inflation but as strategic assets in the energy transition. The result is a feedback loop where scarcity drives speculation, speculation drives prices, and high prices reinforce perceptions of scarcity.

For India, the implications are profound. The slogans of Viksit Bharat and Atmanirbhar Bharat ring hollow when the country remains heavily dependent on imports of critical minerals and lacks globally recognized brands to compel reciprocal market access. India’s trade deals, framed as assertive initiatives, often provide external countries with access to Indian markets without securing equivalent benefits. The India–New Zealand FTA, for instance, promises $20 billion in investment over 15 years, but this translates to barely $1.3 billion annually, insignificant compared to India’s existing FDI inflows of $70–80 billion. Meanwhile, concessions on sensitive imports such as apples threaten domestic horticulture, as seen in Kashmir and Himachal Pradesh. Without indigenous brands or technological leadership, India risks becoming a passive consumer market rather than a proactive producer economy.

The economic data underscores this vulnerability. MSMEs contribute over 30% to India’s GDP and nearly half of exports, yet they face credit constraints and lack access to certification and logistics infrastructure. Rising input costs due to global metal price hikes further erode competitiveness. Copper, essential for electrical equipment and construction, has seen domestic prices rise in tandem with global benchmarks, squeezing margins for small manufacturers. Platinum and palladium, vital for automotive catalytic converters, impose additional costs on India’s automobile sector, which is already grappling with emission norms and global competition. Unless India develops domestic mining capacity, invests in recycling technologies, and builds resilient supply chains, the slogans of self reliance will remain rhetorical.

The geopolitical calculus is equally unforgiving. India’s dependence on Russia for defense equipment and rare metals exposes it to sanctions risk, while reliance on China for electronics and rare earths creates strategic vulnerability. Diversification toward Africa, Latin America, and Southeast Asia is essential, but requires long term investment in diplomatic and economic ties. Nigeria’s currency collapse, from parity with the British pound in the 1980s to extreme depreciation today, illustrates the dangers of resource dependence without diversification. India must avoid similar pitfalls by reinvesting trade surpluses into manufacturing and agriculture, rather than allowing capital flight or speculative bubbles.

The debate among economist’s canters on whether these price surges represent cyclical volatility or structural transformation. Some argue that metals are simply reflecting inflationary pressures and will stabilize once monetary policy tightens. Others contend that the energy transition and geopolitical fragmentation have created a new paradigm where scarcity is permanent and prices will remain elevated. The truth likely lies in between: cyclical factors amplify structural deficits, and without coordinated global investment, volatility will persist. For investors, the erosion of faith in government capacity to stabilize markets is evident. For policymakers, the challenge is to restore credibility through transparent regulation, strategic reserves, and international cooperation.

If these situations are not curbed quickly, the trajectory is clear: all solid materials extracted from the earth will rise beyond expectations, destabilizing industrial economies and undermining sustainable development goals. For India, survival cannot rest on slogans. It requires calculated investment in domestic capacity, scientific innovation in recycling and substitution, and geopolitical agility in securing diversified supply chains. Otherwise, the backbone of the economy—its MSMEs and farmers—will bear the brunt of global competition and resource scarcity, while the promise of Viksit Bharat remains unfulfilled.