Summons in Limbo: SEC Bribery Case Against Adani Hits Diplomatic Wall

Six months after the United States Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) sought India’s assistance to deliver summons to billionaire Gautam Adani, his nephew Sagar Adani, and the Adani Group in connection with an alleged bribery and fraud case, the documents have still not reached their intended recipients. The SEC, in a status update filed on August 11 before the US District Court for the Eastern District of New York, disclosed that it had “requested assistance from Indian authorities to effect service under the Hague Service Convention,” but as of the filing date, “those authorities have not yet effected service.”

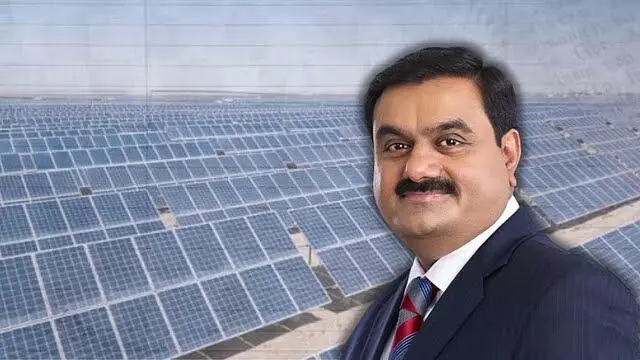

The summons arise from a case filed on November 20 last year, when US prosecutors indicted Gautam Adani, Sagar Adani, and others for alleged bribery, securities fraud, wire fraud, and related conspiracies. At the heart of the SEC’s complaint is the allegation that the defendants paid bribes amounting to Rs 2,029 crore to secure lucrative solar power contracts through India’s Solar Energy Corporation of India (SECI). According to the SEC’s filing, the alleged scheme was not isolated to one region but involved an intricate web of political contacts and commercial maneuvers across multiple states.

The indictment claims that the Adani Group, in concert with Azure Power, colluded to bribe senior officials in Andhra Pradesh, including then Chief Minister Jagan Mohan Reddy. The alleged objective was to secure favorable Power Sales Agreements (PSAs) for solar projects. The SEC’s complaint further describes a series of meetings with state officials from Maharashtra, Kerala, Bihar, Chhattisgarh, Tamil Nadu, Odisha, and Jammu & Kashmir, indicating that the scope of influence-peddling went beyond a single state’s bureaucracy. While the Adani Group and Reddy have categorically denied any wrongdoing, the SEC’s narrative paints a picture of systematic, high-level engagement aimed at distorting competitive processes in India’s renewable energy sector.

The SEC said it had also sent Notices of Lawsuit and Requests for Waiver of Service of Summons, along with copies of the complaint, directly to the defendants and their legal representatives. Moreover, the agency stated that it has “communicated with the India Ministry of Law and Justice” to facilitate the delivery of the documents. Yet, despite this direct outreach, no service has been completed. The SEC, in its latest filing, indicated that it would “continue communicating with the India MoLJ and pursue service of the Defendants via the Hague Service Convention,” underscoring both its persistence and the bureaucratic delay.

The lack of progress has now placed a spotlight on the intersection of corporate power, cross-border legal cooperation, and diplomatic discretion. The Hague Service Convention, to which both India and the United States are signatories, is designed to streamline the process of serving judicial documents internationally. While the convention provides a legal framework, the actual execution depends heavily on the cooperation of national authorities—in this case, India’s Ministry of Law and Justice. The SEC’s statement that the ministry has “not yet effected service” raises questions about the pace and priority given to the matter within the Indian government.

For Washington, the delay represents more than a procedural hiccup; it points to the difficulties of pursuing white-collar crime cases that cross jurisdictions, particularly when the accused are prominent figures with substantial political and economic clout in their home countries. In India, the matter is politically sensitive, not only because of Gautam Adani’s standing as one of the country’s most influential industrialists, but also because of the broader allegations of crony capitalism that have surfaced periodically over the years. While no court in India has so far found Adani guilty of bribery or fraud, the persistence of such accusations from international regulators carries reputational risks both for the conglomerate and for India’s regulatory image.

The SEC’s focus on the renewable energy sector is also notable. India’s solar industry is central to its climate commitments and energy security goals, with SECI playing a key role in allocating contracts for large-scale projects. Any perception that the allocation process is vulnerable to bribery could undermine investor confidence and weaken the credibility of India’s clean energy transition. The alleged Rs 2,029 crore bribe figure, if proven, would represent one of the largest recorded in the Indian renewable sector’s history. For a country seeking billions of dollars in foreign investment to meet its climate targets, the optics of such a case—regardless of its final legal outcome—could be damaging.

The Adani Group has maintained its stance that the allegations are baseless and politically motivated. In prior public statements, the conglomerate has argued that its renewable energy ventures have been built on competitive pricing, operational efficiency, and adherence to legal norms. Similarly, Jagan Mohan Reddy has denied any involvement in wrongdoing, portraying the allegations as unfounded attacks. These denials, however, do little to hasten the procedural steps required to either confirm or refute the SEC’s charges in court. Until the summons are officially served, the case remains in a kind of legal limbo—active in the eyes of the US judiciary, but stalled in practice due to non-delivery in India.

From a legal standpoint, the delay benefits the defense, as it buys time and complicates the SEC’s enforcement timeline. Under US law, timely service of process is a prerequisite for a court to assert jurisdiction over foreign defendants. If service is significantly delayed or deemed impossible, plaintiffs—in this case, the SEC—must seek alternative routes, which are often more cumbersome and less certain.

From a diplomatic perspective, the Indian government’s inaction could be interpreted in multiple ways: as a mere bureaucratic backlog, as reluctance to act against a high-profile business figure, or as a sign of prioritizing domestic considerations over foreign judicial cooperation.

For now, the SEC insists it will keep pressing the Ministry of Law and Justice under the framework of the Hague Service Convention. Whether that persistence will break through the current impasse remains uncertain. What is clear is that this case is about more than one company or one set of contracts—it touches on the credibility of legal cooperation between two major democracies, the integrity of India’s renewable energy procurement process, and the global perception of how India handles allegations of corporate misconduct at the highest levels.

As the legal and diplomatic maneuvers continue, the summons that began as a simple procedural step have become a litmus test for transparency, international cooperation, and the balance between economic power and the rule of law. Until the documents are delivered, the allegations will remain suspended between accusation and adjudication—a reminder that in global corporate law, the gap between filing charges and delivering justice can be as wide as the distance between New Delhi and New York.