From Kolkata to Rajasthan, Quality Failures of Critical Care Devices Raise National Patient Safety Questions

For patients entering government hospitals, trust rests not only in doctors, but also in the medical devices used in treatment. Over the past year, that trust has come under scrutiny in more than one Indian state, as official records reveal quality failures in critical care devices supplied through public procurement systems, detected only after they had entered hospital use.

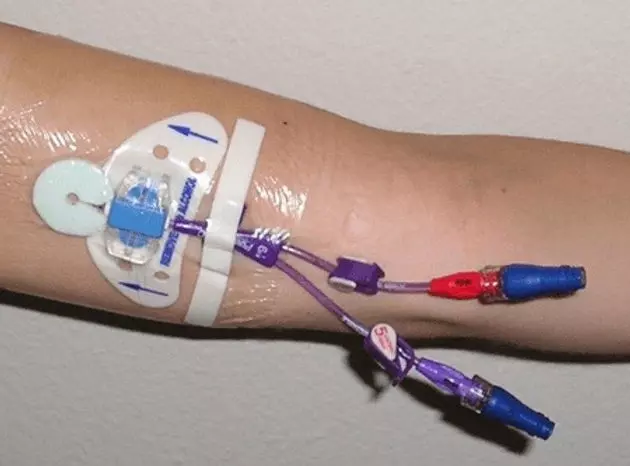

On January 5, 2026, the Rajasthan Medical Services Corporation (RMSC) issued a formal notice directing the recall and replacement of multiple batches of CE-marked PICC catheters supplied by Vygon India Pvt Ltd, the wholly owned Indian subsidiary of a French multinational. The action followed examinations by subject experts, who found that the devices did not meet flow rate specifications prescribed in state tenders. Signed by the Executive Director (Quality Control) and approved by the Managing Director of RMSC, the notice declared the affected batches unfit for use or distribution in medical institutions.

According to the document, the flow rates of the PUR-XRO PICC catheters deviated from tender requirements. RMSC directed that the entire stock of the affected batches be lifted from warehouses and replaced immediately with compliant material.

This action of this State Authority, highlights questions about oversight once devices enter hospital supply chains. In the Rajasthan case, a state authority acted after identifying deviations, with no indication of a national advisory or broader review.

PICC lines are commonly used in oncology, long-term antibiotic therapy, and critical care, where accuracy in flow rate is essential for safe drug delivery. Deviations can affect infusion safety and treatment outcomes, raising concerns about whether similar issues may have gone undetected elsewhere.

The Rajasthan action follows an earlier and even more serious episode in West Bengal. In December 2024, the state government confirmed that inferior quality oximetry CVC catheters had been supplied to major government hospitals, including Calcutta Medical College. Official orders issued by the Directorate of Health Services and Central Medical Stores documented unauthorised substitution of manufacturers and lapses in quality assurance.

That investigation led to the debarment of the distributor involved and a two-year debarment of the French multinational from participating in CMS tenders. The West Bengal government order also observed that the episode “has tarnished the repute of the health system”.

Despite the seriousness of the findings, there was no publicly known directive to review similar supplies in other states. Healthcare observers note that while medical device supply chains operate nationally, regulatory responses remain fragmented and largely state-driven.

The fact that both cases involved internationally certified (CE Marked) devices adds another layer of concern. These were not unapproved products, but devices cleared for use under existing regulatory systems. When quality failures emerge despite such clearances and surface in different states within a short span, they point to a broader warning rather than isolated procurement lapses.

The pattern raises questions about how device safety is monitored after approval. While standards and clearances are defined centrally, oversight appears to weaken once products enter hospital supply chains. In both Rajasthan and West Bengal, state authorities stepped in only after deviations were detected, with no public indication of a wider review beyond the states involved.

For patients, particularly those dependent on public hospitals, such gaps are largely invisible. There is little insight into how devices are procured or monitored, and limited ability to question safety once treatment has begun. When quality concerns surface only through administrative orders issued after the fact, they risk undermining confidence in the healthcare system.

In both cases, the state acted after the failure was identified. What remains unresolved is who is responsible for identifying such risks earlier, before devices reach patients, and whether warnings detected in one part of the country are being shared and acted upon elsewhere. More importantly the State Procurement authorities have protected the patients in the government hospitals of their state, what about 75% of India’s patients lying in Private Hospitals. Who will protect them? Who will alert the Private Hospitals? The CDSCO must answer.