Toxic Trust: How India’s Drug Watchdogs Became Lapdogs

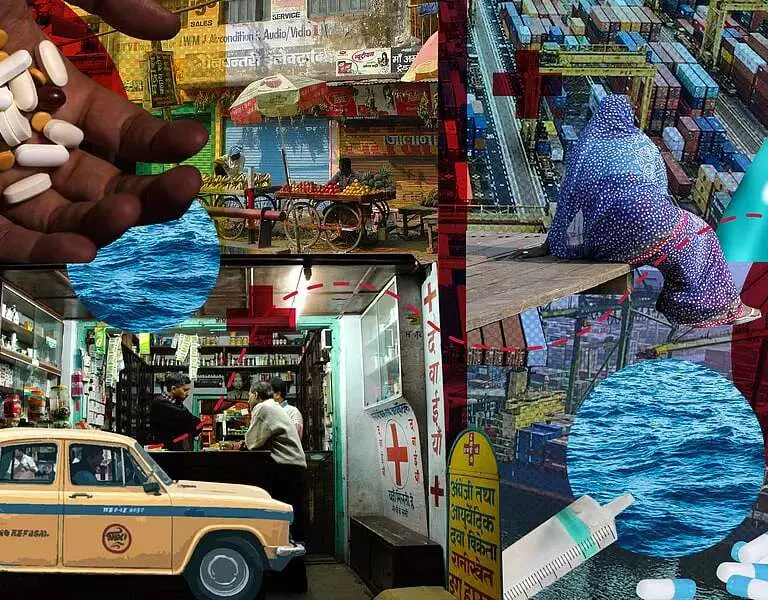

In India, where a pharmacy shelf often doubles as a political ledger, the recent raids by the Central Drugs Standard Control Organisation (CDSCO) that led to the banning of 60 medicines reveal the uncomfortable intersection of commerce, corruption, and political calculation. What appears to be a moral crusade against substandard drugs is, on closer scrutiny, a spectacle — a performance of regulation rather than its practice. Behind the rhetoric of vigilance lies a machinery that thrives not on prevention, but on selective outrage.

The CDSCO’s monthly alerts on failed drug samples are meant to reassure the public that the system is working. Yet, these announcements resemble ceremonial confessions rather than accountability. If the watchdog were truly awake, how did diethylene glycol-laced cough syrups reach the shelves and claim the lives of 48 children? How did Patanjali continue selling 212 misleading products until courts intervened? Why do spurious and mislabeled drugs continue to circulate freely in New Delhi — a city where counterfeit capsules are as common as pollution masks? The answer, it seems, lies in a system that punishes exposure, not negligence.

The deeper problem is structural. India’s drug regulation functions through a fragmented network of state and central authorities that often operate in silos. Manufacturing units exploit this gap, hopping jurisdictions to avoid scrutiny. Sampling and testing — the backbone of regulation — are far from random. Insiders confirm that companies are routinely tipped off before inspections, ensuring that only “clean” batches reach the labs. When a batch fails, it is quietly recalled without naming or shaming the company, and business resumes as usual.

The Drugs and Cosmetics Act of 1940 empowers the government to prosecute violators and suspend licenses, but these provisions remain largely ornamental — used more as political levers than instruments of justice. Pharmaceutical giants like Cipla, Alkem, and Macleods — names that dominate both markets and political donations — have seen repeated test failures without facing blacklisting or public censure. The failure here is not of law, but of will. Enforcement becomes selective when regulation is shielded by the very political class that benefits from its opacity.

According to data from the Association for Democratic Reforms (ADR), major pharmaceutical companies have poured crores into political coffers through anonymous electoral bonds. These contributions surge precisely when elections approach, as is the case now with West Bengal and Tamil Nadu. The coincidence of regulatory raids and electoral cycles is too patterned to be dismissed as chance. It suggests a calculated choreography — where the state flexes its moral authority at moments most electorally profitable, not when citizens’ lives are at risk.

This political insulation of the pharmaceutical industry breeds a culture of impunity. In India, substandard drugs are not merely administrative lapses; they are silent assassins, claiming lives invisibly and unrecorded. When a toxic syrup kills children, the outrage is momentary. Headlines fade, commissions are formed, and reports gather dust. Meanwhile, the same manufacturers continue to supply hospitals and pharmacies.

The government claims reform through circulars and advisories, but there is no public dashboard to track failed medicines, no SMS alerts to warn consumers, and no pharmacist held responsible for selling rejected stock. Transparency is replaced with technical jargon, and accountability is buried under bureaucratic procedures.

This isn’t just a regulatory crisis — it’s a moral one. The Indian pharmaceutical sector, often hailed as the “pharmacy of the world,” exports life-saving drugs across continents while its domestic regulation allows life-taking ones to circulate within. The contradiction is staggering: a nation celebrated for its generics abroad cannot guarantee purity at home. The system’s selective blindness reflects not incompetence, but complicity.

When regulation becomes a tool for optics, and punishment a matter of political convenience, every ban becomes a ritual rather than a reform. The human cost of this charade is immeasurable. Every time a mother buys a syrup for her child, or a diabetic relies on an insulin vial, there is an implicit contract of trust between citizen and state. That trust is being systematically betrayed.

Oversight today is a sieve, not a shield. It filters publicity, not poison. The tragedy is that reform is not technologically impossible — what’s missing is the moral will to separate governance from influence. A truly independent CDSCO would make inspection reports public, mandate QR-coded packaging to verify authenticity, and blacklist habitual offenders irrespective of their political connections.

None of this requires new laws — only the courage to enforce existing ones. Until that courage emerges, raids and bans will continue to be televised symbols of virtue, not acts of justice. The pharmaceutical “dhandha” will thrive under the disguise of regulation, while the public swallows both medicine and manipulation.

The real illness in India’s drug industry is not contamination — it is collusion. The question is no longer whether the CDSCO is functioning; it is for whom it functions. And until that answer changes from “patrons” to “people,” every pill in this country will carry not only a dose, but a doubt.