UGC Draft Under the Legal Lens: Politics, Process and the Limits of Executive Power

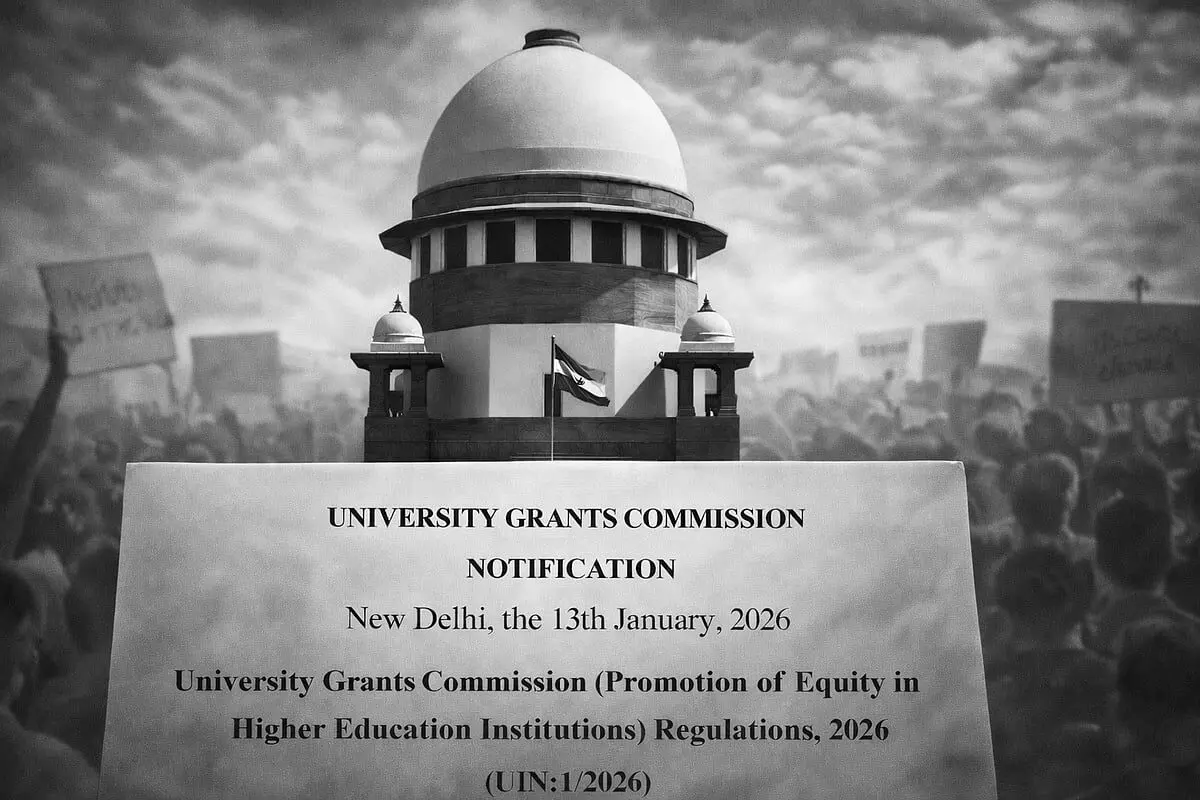

The controversy surrounding the proposed changes to the University Grants Commission (UGC) framework has moved swiftly from academic corridors to the centre of India’s political and constitutional discourse. What is being debated today is not merely a policy document, but the legal architecture through which higher education is governed, and the constitutional discipline that binds both the government and the opposition.

At the heart of the issue is the manner in which committees are constituted to draft laws and regulatory frameworks. Under established parliamentary practice, committees often include members from the ruling side as well as the principal opposition. This is intended to ensure transparency, institutional balance and constitutional legitimacy. Once a draft is produced through such a process, the government’s room for unilateral withdrawal becomes legally constrained. Any abrupt rollback risks inviting allegations of arbitrariness and violation of constitutional procedure.

Legal experts point out that a regulation prepared through a constitutionally valid process cannot be scrapped overnight merely on political discomfort. It must either be amended through due process or subjected to judicial scrutiny. This is why the present situation places the Union government in a delicate position: acting too fast could be portrayed as executive overreach, while acting too slowly could intensify public discontent.

The protests against the UGC framework, particularly from sections of society that believe the draft is socially imbalanced or legally flawed, have brought another dimension to the issue. From a legal standpoint, peaceful dissent is protected by Article 19 of the Constitution. However, the state also carries a constitutional obligation to ensure that demonstrations do not slip into disorder or become vehicles for political manipulation.

Senior advocates note that the most legally sustainable route for the government would be to constitute a high-level review committee comprising constitutional experts, educationists and retired judges. Such a body could examine whether the draft violates principles of equality, federal balance or institutional autonomy. Its recommendations would then provide a defensible basis for either amendment or withdrawal.

Another path, increasingly discussed in legal circles, is judicial intervention. A Public Interest Litigation (PIL) challenging the UGC framework on grounds of constitutional infirmity would shift the matter into the Supreme Court’s jurisdiction. This would remove the burden of unilateral decision-making from the executive and place it within the neutral domain of constitutional adjudication.

What is significant is that the present conflict is less about ideology and more about constitutional mechanics. The government cannot ignore the legal pedigree of a draft that has passed through formal committee procedures. At the same time, the opposition cannot assume that participation in drafting insulates a framework from judicial review.

In legal terms, the UGC controversy resembles a classic constitutional dilemma: how to correct a potentially flawed policy without undermining the credibility of institutional processes. It is a test of restraint as much as of authority.

For the government, the challenge lies in proving that corrective action, if taken, is rooted in law and not in political expediency. For the opposition, the challenge is to demonstrate that criticism is based on constitutional substance rather than political advantage.

In a democracy governed by law, no regulation—however contentious—can be dismantled through rhetoric alone. It must pass through the filters of procedure, judicial reasoning and constitutional morality. That is where the real battle over the UGC framework is now being fought: not on the streets, but in the quiet, rigorous language of the Constitution.