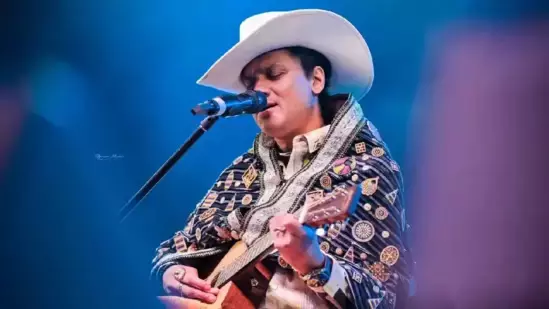

Zubeen Garg: The Tragic Bohemian and the Politics of Death

Zubeen Garg was not born to be managed. He was a storm disguised as a singer — a bohemian spirit who lived with reckless purity. To the corporate world, he was not a poet or prophet, but a product: a name that could sell tickets, attract sponsors, and justify CSR budgets. The show business ecosystem around him — event managers, bureaucrats, ministers, and middlemen — built an economy on his charisma. They called it culture, but it was commerce in its finest disguise.

Behind the arclights, a parallel economy flourished. State departments funded music festivals and cultural galas with public money, packaged under tourism promotion or youth engagement. The corporate sector poured millions under the soft cover of social responsibility. The result — a well-oiled cycle where emotions were monetised and music became a balance-sheet entry. Zubeen, the soul of Assam, was the centrepiece of this economic theatre.

Then came the unnatural death in a foreign land — abrupt, inconvenient, and politically explosive. A half-truth, half-lie story unfolded like a badly written screenplay. The stage that once echoed with applause became a courtroom of whispers. Hidden hands, powerful names, and a murky media choreography took charge. The death of a singer turned into the birth of a narrative.

For society, Zubeen was not just a musician; he was a blood cell circulating through the Assamese identity — from the child in school to the grandfather in a rural courtyard. His songs were not performances; they were collective emotions. Yet, within days, grief was converted into strategy. Emotions were harvested, condensed, and repackaged — the first raw material of politics.

When the name of the Chief Minister’s wife surfaced, the theatre widened. Politics over the dead has always been India’s comfort zone. But here, it crossed into a new moral vacuum — the death of empathy and the rise of electoral opportunism. The truth was not buried — it was auctioned.

In the months that followed, the Zubeen case became more than a tragedy; it became a mirror reflecting the state’s decaying ethics. Instead of a transparent investigation, there emerged a battle of perception. The artist’s death turned into a corporate-political case study — of how memory can be monetised and mourning can be marketed.

The political economy around Zubeen’s death exposed a dangerous truth — that Assam’s new elite class is no longer driven by ideology or intellect, but by contracts, events, and control over narrative industries. Music, cinema, and festivals have become tools of patronage — the modern-day replacement for oil, timber, or coal. A new kind of cultural oligarchy has formed — funded by the government, endorsed by corporations, and managed by influencers.

And in this transformation, Zubeen stood like a Greek tragic hero.

Like Orpheus, the divine musician of myth, he descended into the depths — believing that his song could bring light to darkness. But like Orpheus, he was betrayed by fate, consumed by the underworld of deceit. Orpheus lost his life but not his name. Zubeen too — destroyed by the machinery that once celebrated him — lost his breath, but not his legacy.

Zubeen’s death has thus become a referendum on Assam’s moral economy. It asks: who owns our art, our icons, and our grief? It reminds us that culture without conscience is just commerce, and politics without empathy is theatre without a soul.

In a state where emotion has always been a form of resistance, Zubeen’s silence now speaks louder than any speech. He was not merely a musician; he was the soundtrack of a society struggling between nostalgia and modernity.

In the end, he became what the Greeks called Katharsis — a purifying pain.

A man who lost his life, but not his name.

A melody the system could not silence.

A truth the powerful could not bury.