Caste Census and the Mandal Legacy: Reigniting the Debate on Social Justice in India

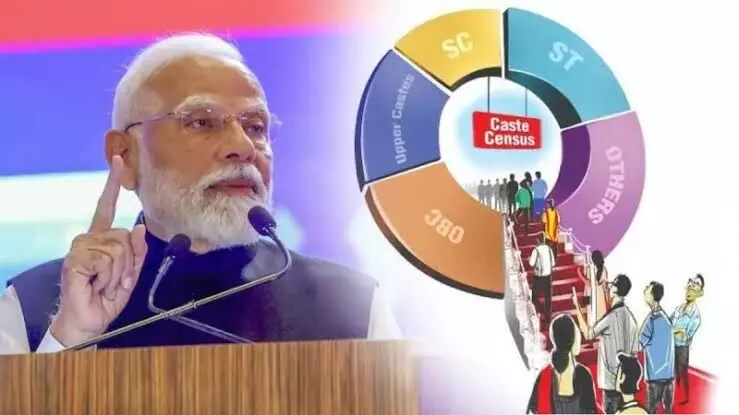

The Indian government’s recent decision to approve a caste-based census has reopened a deeply contested and politically significant debate around affirmative action, social justice, and the legacy of the Mandal Commission. After years of resistance, the move marks a major shift in the ruling party’s stance and has triggered widespread discussions about the future of reservation policies, representation of backward classes, and the necessity of updated caste data in India’s policy-making framework.

The Mandal Commission, officially known as the Second Backward Classes Commission, was established in 1979 under the chairmanship of B.P. Mandal to identify socially or educationally backward classes and recommend steps for their advancement. Its landmark proposal to provide 27% reservation to Other Backward Classes (OBCs) in government jobs and educational institutions was implemented in 1990 by Prime Minister V.P. Singh.

This decision transformed Indian politics, empowering backward castes but also triggering intense backlash, particularly from upper-caste communities, leading to nationwide protests and even instances of self-immolation by aggrieved students. Despite the turbulence, the implementation of Mandal Commission recommendations brought greater representation to marginalized communities in public institutions and reshaped the nature of Indian democracy.

However, over the decades, many of the Commission’s broader recommendations have remained unfulfilled. These include reservation in the private sector and judiciary, as well as a systematic mechanism to evaluate and update the socio-economic status of backward communities. In the absence of regular and transparent caste data, the existing reservation system continues to operate on outdated assumptions. This is where the relevance of the caste census becomes paramount. Without accurate data, how can policies be framed to address real inequality? As sociologist Satish Deshpande has pointed out, "In a country where caste determines access to opportunity, pretending it doesn’t exist in data collection is both dishonest and harmful."

Despite its historical importance, caste enumeration was discontinued after Independence. The last official caste count occurred in 1931 under British rule. Although the Socio-Economic and Caste Census (SECC) was conducted in 2011, its caste data remains unpublished, allegedly due to concerns over its accuracy and political sensitivity. The present government’s U-turn—agreeing to a caste census after previously rejecting it as divisive—is widely seen as a strategic move, especially with crucial state and national elections approaching. It is no coincidence that this decision comes amid mounting pressure from opposition leaders such as Tejashwi Yadav, who have consistently demanded not only a caste census but also an expansion of reservations based on the findings. Yadav, in a letter to Prime Minister Narendra Modi, even called for reservations in the private sector and judiciary—long-standing yet unfulfilled proposals from the Mandal era.

The demand for a caste census has also revived the contentious debate around the 50% cap on reservations imposed by the Supreme Court in the Indra Sawhney case of 1992. The Court ruled that exceeding this limit would compromise the principle of merit and violate the Constitution’s equality clause. Yet, this cap has been increasingly questioned in recent times, especially after the 103rd Constitutional Amendment Act introduced a 10% quota for Economically Weaker Sections (EWS) among upper castes, which took the total reservation beyond 50% in many states. Congress leader Rahul Gandhi has called for the removal of the cap, arguing that the socio-economic realities of India's backward classes, Dalits, and Adivasis are far too vast and complex to be confined within an arbitrary ceiling. He stated, "The real backwardness in India is not capped at 50%—then why should affirmative action be?"

This has added fuel to an already volatile debate. For many, the caste census is not merely a statistical exercise but a moral and political imperative. It is seen as the first step towards acknowledging and correcting historical injustices that continue to haunt India’s development story. Political scientist Christophe Jaffrelot has argued that the "Mandal moment" helped democratize Indian politics by empowering marginalized castes, but without robust data and expanded representation, these gains risk stagnation. On the other hand, critics of the caste census argue that it could further entrench caste identities, polarize communities, and shift focus away from economic and developmental issues.

However, these concerns seem increasingly out of sync with ground realities where caste remains a critical determinant of opportunity and access.

The political ramifications of the caste census are already evident. While the opposition sees it as a rallying point to consolidate backward caste support, the ruling BJP’s endorsement is viewed by analysts as a tactical response to electoral arithmetic rather than a commitment to social reform. Pratap Bhanu Mehta aptly notes that “the caste census is no longer a moral question—it has become a political inevitability.” Still, the question remains whether this political consensus will translate into substantive reforms or if the census will become another symbolic gesture without policy follow-through.

As the nation moves toward implementing this long-overdue data collection, the caste census has opened up critical questions about the nature of Indian democracy. Will the data lead to a more just and inclusive society, or will it become fodder for short-term political gains? Will the government act on the findings to reconfigure its reservation policies and welfare schemes, or will it bury the data as was done in 2011? These are questions that will determine the true legacy of this decision.

In the final analysis, the caste census represents an opportunity for India to confront the truths of its social fabric and to design policies grounded in empirical realities rather than political convenience. Whether it leads to a new phase of social justice or remains another deferred promise will depend not just on data collection but on the political will to act upon its findings.