The Invisible Citizen: Muslim Welfare and the Crisis of Inclusion in India

In 2006, the Sachar Committee made a quiet but piercing observation: “In certain areas, the condition of Muslims is worse than that of Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes.” Nearly two decades later, that truth still echoes—not with outrage, but with a haunting silence. What’s changed is not so much the facts on the ground, but the willingness to see them.

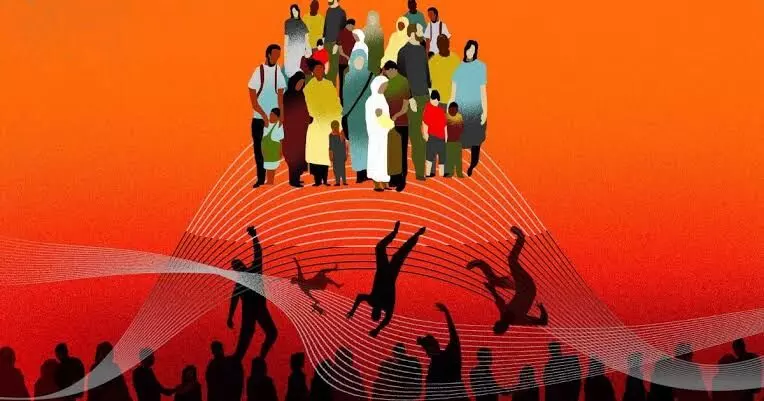

India’s promise of secularism was never perfect, but it carried a moral clarity. It aimed to give every citizen—regardless of faith, caste, or background—dignity and a fair chance. Today, that promise feels unevenly delivered, especially for the country’s 200 million Muslims. Their presence in the public discourse is often hyper-visible during times of controversy, and yet practically invisible when it comes to targeted welfare, development, or political participation.

A Long History of Being Left Behind

The post-Independence journey of Indian Muslims has been shaped by both internal and external forces. Partition left deep social, psychological, and economic scars. Over the decades, the community has found itself at the crossroads of political neglect and social suspicion. While the Constitution promised equal rights, ground realities often told a different story.

During the 1980s and 1990s, communal tensions, economic liberalization, and growing majoritarian politics left large sections of the Muslim population isolated. Educational and employment indicators remained low, and many Muslims stayed confined to informal, low-paying sectors such as tailoring, welding, or artisanal trades. The Sachar Committee laid this bare: Muslims had lower literacy rates, poorer access to healthcare and credit, and minimal representation in public institutions. It was a matter of systemic failure, not religious identity.

Inclusion Gaps Are Not Exclusive

To be clear, exclusion in India is not a uniquely Muslim experience. Many marginalized communities like Dalits, Adivasis, the rural poor, struggle with underinvestment, bureaucratic apathy, and social discrimination. Welfare delivery has long been plagued by inefficiencies, leakages, and tokenism. In recent years, growing urbanization and digital governance have added new hurdles for the very people who most need the state’s support.

Within the Community: Hard Questions, Too

It would be unfair and unwise to place all the responsibility on the state alone. Leadership within the Muslim community has not always risen to the challenge. Political figures have often relied on grievance-based politics without offering a developmental vision or building broader coalitions.

Religious leadership, too, has sometimes resisted reform in areas such as modern education, women’s rights, and public engagement.

This internal stagnation has made it easier for dominant narratives to caricature the entire community as either passive victims or unwilling participants in national development. The truth is far more complex. There are Muslims innovating, leading businesses, teaching in schools, and serving in the army. But these stories are rarely amplified.

Shrinking Voice, Rising Anxiety

Muslims today are part of every sector of Indian society, but their political representation is in decline. In the current Lok Sabha, they form less than 4 percent of MPs, far below their 14 percent share of the population. Many parties, wary of polarization, have quietly dropped Muslim candidates altogether.

In everyday life, too, the sense of scrutiny has grown.

From housing discrimination to debates over dietary habits or attire, many Muslims speak of an unspoken anxiety in public spaces. Policies like the Citizenship Amendment Act and conversations around the Uniform Civil Code are viewed with mistrust, compounded by incidents where state actions appear selectively harsh. These perceptions may not always reflect the intention of policymakers, but the impact on the ground is undeniable.

Beyond Neutrality: Towards Equity

A growing idea in governance is that welfare should be religion-neutral, and in principle, that is correct. But neutrality cannot mean blindness to disparity. If certain communities start at a historical disadvantage, treating everyone the same only maintains inequality.

Consider a Muslim girl wearing a hijab turned away at a job interview. Or a student who cannot get a loan or access coaching centres. Or a family who is denied a home by a landlord despite the ability to pay. These are not abstract injustices. These are daily realities, and they require policy responses informed by evidence, not ideology.

The Way Forward: A Shared Democratic Project

India must return to the practice of data-driven, community-sensitive policymaking, which is inclusive rather than divisive. Welfare must be judged beyond announcements, by its access, uptake, and impact. Accountability mechanisms, transparency, and civic participation must be strengthened across the board.

At the same time, Muslim leadership must move beyond rhetoric and invest in education, entrepreneurship, and civic engagement. The community cannot afford to be insular. It must demand its place at the table—not through fear or identity politics, but by laying claim to the Constitution’s promise.

This is not just about Muslims. It is about whether Indian democracy can accommodate difference, dissent, and diversity while remaining just. A nation that sidelines any group through neglect or silence is not a fully functioning democracy. The health of our republic depends on making every citizen, regardless of faith, feel counted, heard, and valued.

(The writer is a versatile content professional with 20+ years of experience, specializing in customized, high-impact writing across education, PR, corporate, and government sectors.)