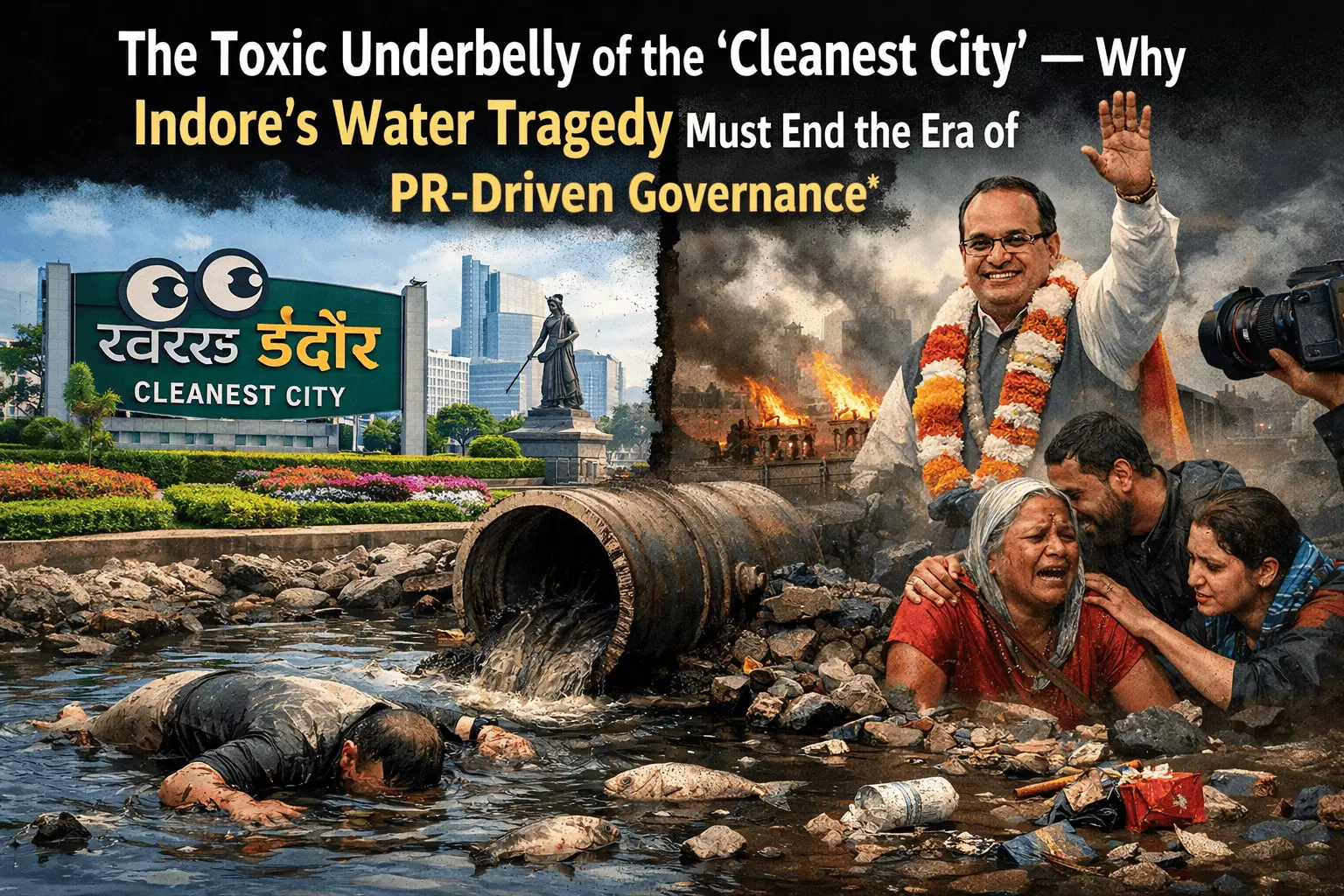

The Toxic Underbelly of the "Cleanest City" — Why Indore’s Water Tragedy Must End the Era of PR-Driven Governance*

For eight consecutive years, Indore has stood atop the podium of India’s Swachhta Survekshan, a gleaming testament to urban management, waste segregation, and civic pride. To the outside world, Indore is a model city, a seven-star success story often showcased to international delegates as the gold standard of the Swachh Bharat Mission. But this week, the gold-plated facade of the "Cleanest City" cracked, revealing a reality as dark and murky as the water currently flowing through the taps of Bhagirathpura.

As we usher in 2026, the city is not celebrating another milestone of urban development. Instead, it is counting bodies. At least seven people—including a six-month-old infant named Avyan—are dead. Over 1,100 others are battling for their lives in hospitals, their bodies ravaged by the cruel onset of water-borne pathogens. This is not a natural disaster or an act of God; it is a systemic, administrative execution.

The preliminary investigation into the Bhagirathpura tragedy reads like a textbook on how not to build a city. A main drinking water pipeline was found running directly beneath a public toilet. In a display of staggering incompetence, the toilet was reportedly built without a mandatory septic tank, and its waste was being channeled into a pit sitting precariously above the water line. When a leak developed in the drinking water pipe, the inevitable occurred: human excrement mixed with the city’s potable supply. For days, residents complained that their water smelled foul and tasted bitter. They were ignored. In a city that prides itself on "real-time monitoring" and "smart governance," the cries of the poor were muffled by the celebratory noise of the latest rankings. It was only when the death toll began to mount that the machinery groaned into action, offering the usual cocktail of mid-level suspensions and ex-gratia payments.

The tragedy raises a fundamental, uncomfortable question: How can a city be the cleanest in a country while its citizens are dying from consuming its water? The Swachhta Survekshan has long been criticized for its heavy focus on visible cleanliness—swept streets, painted walls, and door-to-door garbage collection. However, urban sanitation is not just about the garbage on the road; it is about the integrity of the pipes beneath it. By rewarding cities primarily for aesthetic improvements and PR-friendly initiatives, the survey has inadvertently encouraged municipal bodies to prioritize what can be seen by a visiting auditor over what actually keeps a population healthy.

If the survey parameters do not strictly account for the separation of sewage and water, then the rankings are not just flawed; they are dangerous. They provide a false sense of security to citizens and a shield for administrators to hide behind. The obsession with being Number One has created a culture where data is massaged and problems are buried to maintain a winning streak. This "ranking-first" mentality has replaced "safety-first" governance. We have become a nation of cities that look good in drone shots but fail the test of a simple glass of tap water.

The response from the state leadership has followed a weary, predictable script. There have been expressions of grief and promises of compensation, but "mistake" is a sanitized word for the criminal negligence of building a latrine over a lifeline. Indore does not need more trophies; it needs an audit of its soul. We must move beyond the vanity of the Super Swachh League and demand a Safe City League. Infrastructure transparency must become the new metric. Every inch of the water and sewage network needs to be mapped and made public to prevent "accidental" intersections. We must also demand criminal liability for senior officials who approve projects that violate basic engineering safety codes, rather than allowing them to use junior engineers as scapegoats.

The Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs must immediately overhaul the Swachhta metrics. Any city that records a death due to preventable water contamination should be disqualified from the top tier of rankings, regardless of how clean its central squares appear. Real cleanliness is not the absence of litter on a sidewalk; it is the absence of toxins in a child’s drink.

The families in Bhagirathpura are not just victims of a pipe leak; they are victims of a culture that values the image of a city over the individuals living in it. As the National Human Rights Commission takes cognizance and the High Court demands answers, the citizens of Indore must also wake up. We must stop being satisfied with the "Cleanest City" tag if that tag is bought with the lives of our neighbors. Until every tap in every colony pours out water that is truly life-giving, the trophies in the Municipal Corporation office are nothing more than hollow pieces of metal.

Indore is at a crossroads. It can continue to chase the vanity of rankings, or it can finally do the hard, invisible work of ensuring that "clean" actually means "safe." For Avyan and the others who died this week, the choice has already been made—too late. The rest of us must now decide if we will continue to ignore the rot beneath the surface in exchange for a shiny title.