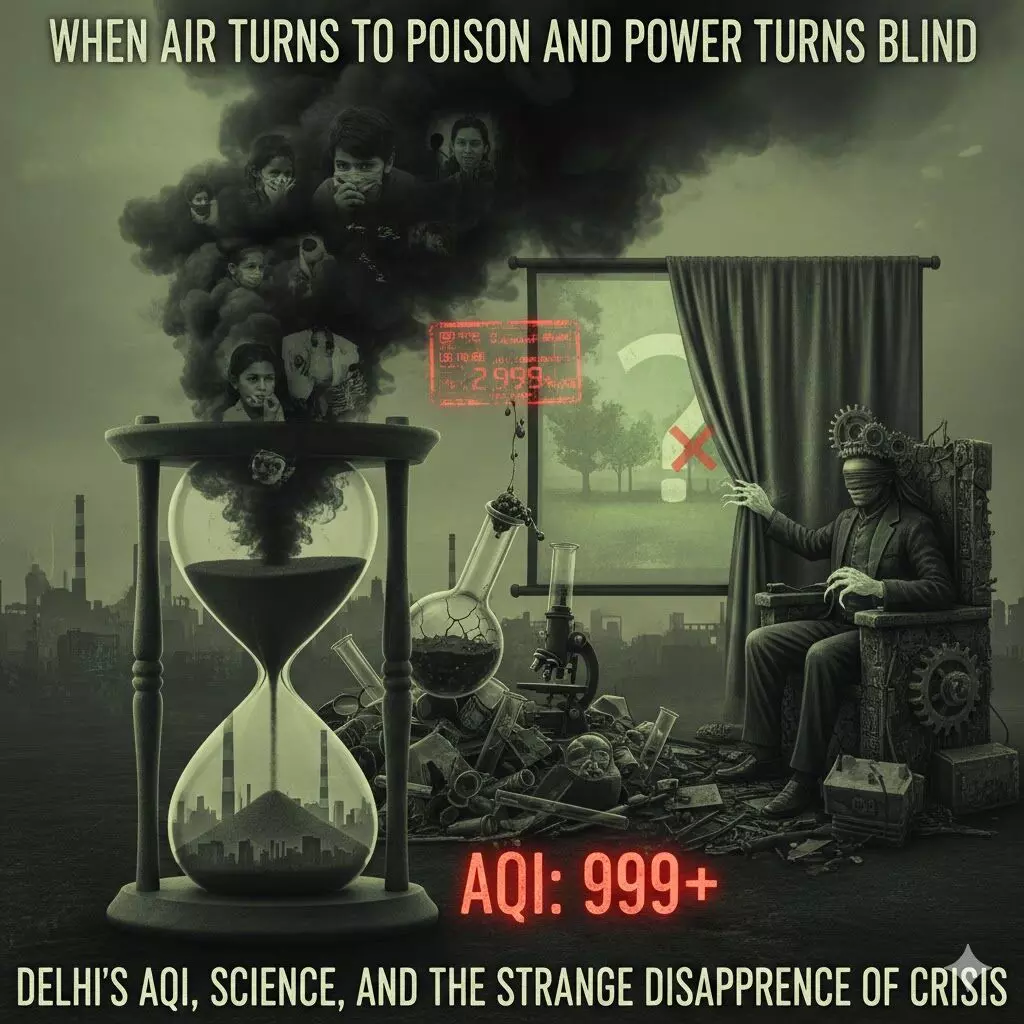

When Air Turns to Poison and Power Turns Blind: Delhi’s AQI, Science, and the Strange Disappearance of Crisis

Delhi’s air has once again crossed from “dangerous” into the territory of slow-motion catastrophe. Yet the political language surrounding it has become curiously hollow. The AQI numbers rise like a medical emergency chart—350, 420, 480—each unit translating into measurable damage to lungs, blood vessels, hearts and even unborn children. Scientifically, there is no ambiguity left about what this air does to the human body. Politically, however, ambiguity has become a chosen refuge.

What makes this moment especially unsettling is not merely the toxicity in the air but the sudden disappearance of political urgency—particularly after the reins of power shifted into BJP hands under Chief Minister Rekha Gupta.

From a health-science perspective, Delhi’s air at an AQI above 300 is not just “bad”; it is classified as “hazardous.” At PM2.5 concentrations often exceeding 10–15 times the WHO-prescribed safe limit, microscopic particles penetrate deep into the alveoli, cross into the bloodstream, trigger systemic inflammation, thicken blood, disrupt heart rhythms and accelerate atherosclerosis. Peer-reviewed studies from AIIMS, ICMR and The Lancet Planetary Health have repeatedly shown that long-term exposure to Delhi’s air reduces average life expectancy by 9 to 11 years. On high-smog days, emergency admissions for asthma, COPD, heart attacks and strokes rise by 20–30%. Children growing up in this environment show reduced lung capacity even before adolescence. These are not ideological claims; they are epidemiological facts.

What is rarely acknowledged in political speeches is that air pollution does not kill dramatically—it kills quietly. It weakens the elderly just enough to make winter fatal. It increases low birth weight. It pushes borderline cardiac patients over the edge. It does not announce death with fire or flood; it erodes survival invisibly. Yet year after year, Delhi slips into this gas chamber with ritualistic predictability.

Now comes the political inversion demanding scrutiny. For nearly a decade, the BJP declared Delhi a symbol of administrative collapse. The Yamuna was portrayed as a septic disgrace. Water contamination was cited as proof of criminal negligence. Smog was framed as a governance failure. Every municipal-election campaign weaponised garbage mountains, sewage, chemical foam on the river and choking air as daily indictments of those in power.

And now, under a BJP Chief Minister, Delhi’s air is suddenly being treated as an almost abstract inconvenience.

This is where the contradiction becomes impossible to ignore. Rekha Gupta rose through the politics of the street and the ward—the corporator’s politics where clogged drains, garbage rot, traffic chaos and polluted air are not data points but lived humiliation. Corporators breathe the same air as sanitation workers. They wade through the same waterlogged streets. They face the same angry shopkeepers and coughing schoolchildren. Their authority is built on proximity to suffering.

But the moment the corporator becomes Chief Minister, a strange alchemy occurs: the crisis dissolves into silence.

The question writes itself with surgical clarity: Did pollution magically vanish the day the BJP took charge, or has the definition of “crisis” quietly shifted? If the Yamuna was poison yesterday, is it now suddenly holy? If Delhi’s water was toxic under one regime, is it medicinal under another? If AQI above 450 was once a scandal, is it now merely a seasonal inconvenience?

This is not merely hypocrisy. It represents a deeper distortion in Indian governance—the selective visibility of suffering. Environmental disasters are no longer measured by scientific thresholds but by political convenience. AQI does not change chemically with the government, but its political weight does. Under one dispensation, pollution becomes a national outrage. Under another, it becomes “North India’s winter phenomenon,” a phrase that itself defies scientific scrutiny.

Let us be precise. Delhi’s pollution is not an act of God. It is the result of accumulated policy failures—vehicular density without emission discipline, construction without dust control, industrial clusters running on outdated fuel, stubble burning unmanaged at scale and urban planning that traps pollutants in low-wind corridors. These are engineering and administrative failures, not metaphysical ones. Any government pretending helplessness is confessing either incompetence or indifference.

What makes the present moment analytically disturbing is the collapse of political pressure precisely when pressure is most needed. The same BJP ecosystem that once demanded resignations over smog now offers explanations, deflections and weather-based excuses. This does not absolve previous administrations; it merely exposes how pollution has been transformed from a public-health emergency into a partisan instrument.

Science does not recognise party flags. PM2.5 does not check voter lists before entering lungs. Nitrogen dioxide does not distinguish between BJP and non-BJP households. Inflammation markers in the blood do not respond to political slogans. And yet leadership behaviour suggests visibility itself has become politicised. When a disaster is no longer named, it is effectively erased from the moral ledger.

The cruelty of this erasure becomes evident in government hospitals, where beds fill with breathless patients during smog peaks; in low-income neighbourhoods, where families cannot afford air purifiers or PM2.5-grade masks; and in roadside shelters where night-time exposure is total. These people do not experience “seasonal variation”; they experience respiratory collapse.

The unspoken insinuation now seems to be that power itself detoxifies reality—that once the BJP occupies the chair, the poison loses toxicity. This is not governance; it is narrative laundering. If such a principle is accepted, every failure in India becomes solvable not by reform but by rebranding.

Delhi today is not merely choking on polluted air; it is choking on political denial. When leaders stop acknowledging danger, danger becomes permanent. The air does not need slogans—it needs relentless, uncomfortable accountability. Until that returns, the real pollution hovering over Delhi will not just be chemical. It will be moral.