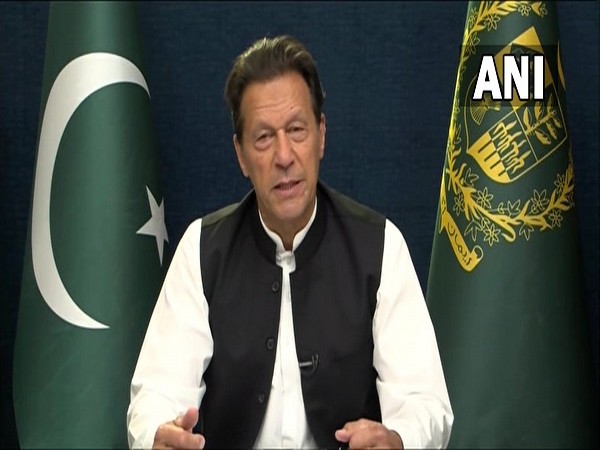

Pakistan's ousted PM Imran Khan playing dangerous game, argues former Afghan envoy

Islamabad [Pakistan], April 21 (ANI): Former Afghanistan Ambassador Jawid Ahmad said that ousted former Prime Minister of Pakistan Imran Khan made 'dangerous allegations' by accusing the United States of plotting conspiracy against him.

In an opinion piece, written along with Douglas London, a professor at Georgetown University's School of foreign service, he argued that Khan's toxic nationalist politics has already dangerously polarized the country. The dissolution of government and ouster of cricketer-turned-politician from the National Assembly, as a result of the no-confidence motion, has made him emerge as an even more dangerous loser, they stated.

As Prime Minister, Imran Khan treated his government like a cricket game, that is, as a one-man show, they reasoned, adding that despite losing the parliamentary majority on March 30, he refused to recognize the mismanagement of the economy, foreign-policy mishaps, and disagreements with his military overlords that had crumbled the walls of his political sandcastle.

Instead, he persisted by deploying various schemes to remain in power, including cooking up a narrative of a U.S. conspiracy to evoke Pakistani nationalism and patriotism as a force multiplier. Khan even attempted to prolong the parliamentary proceedings to further stir political chaos and possibly convince Pakistan's powerful military to declare martial law, states the Report further.

"Khan's statement has sparked the dangers of countless smouldering fires across Pakistan's political, religious, and militant spectrums waiting to be lit," they added.

After the reign of Imran Khan came to an end, the political drama that unfolded in the country leading up to the ouster of the country's Prime Minister shows that the former Pak PM will go to just about any lengths to hold on to power. After the fall of his government, Imran Khan started a countrywide protest campaign in two successive rallies in Peshawar and Karachi this month, urging a large number of people to attend.

"Pakistan became an independent state in 1947, but the freedom struggle begins again today against a foreign conspiracy of regime change," Khan tweeted shortly after his ouster. He declared he would not accept "US-backed regime change" that "brings into power a coterie of pliable crooks," branding his political opposition "national traitors" and the new caretaker setup an "imported government."

While stoking Pakistan's anti-Americanism domestically, he used the Army as his political muscle to wrest Pakistan's politics out of the hands of dynastic elites, mostly through his anti-corruption campaign.

It is likely that Khan aspired from the outset to ultimately push the generals aside and played with them, rather than aiming to settle for being their frontman. Imran Khan also used his platform to exploit anti-India nationalism to deliver his young, conservative, urban, middle-class constituency to his cause in support of the military.

By overstepping into the military's turf, by not granting Bajwa's term extension, Khan committed a major blunder, they claimed. Pakistan's divided political opposition interpreted these civil-military tensions as the end of Bajwa's support for Khan, which allowed the opposition to consolidate and remove Khan in military-endorsed parliamentary proceedings. Khan's manoeuvres have thus far proved fruitless, said Douglas.

Islamophobia and Khan's outspoken behaviour on it has supported Pakistan's blasphemy laws. While condemning Western values as antithetical to Pakistani values, he mainstreamed political Islamism by funding madrassas and introducing a single national curriculum that combined regular and religious schooling. His policies aligned with what the Army has long been doing itself as a means of promoting anti-Indian nationalism and as a recruitment ground for the jihadi groups it supported.

The report by FP suggests Imran Khan's keenness to restore Pakistan's place as a Muslim welfare state that resembles the seventh-century Medina.

Meanwhile, the generals have also long played with fire by facilitating regional jihadi groups and encouraging conservative Islamic fervour at home. In doing so, the generals have outdone themselves in franchising militancy.

Despite Khan's removal from power, he continues to command greater control and legitimacy over his large conservative and extremist constituency and has no compunction about intensifying his anti-American rhetoric and weaponizing Pakistani nationalism to solidify his base in support of his cause.

The perennial Pakistani mistrust of Washington as a partner remains a serious issue, and the next Pakistani government will have to figure out the kind of partnership it wants to develop with the United States.

Other challenges include Pakistan's state-directed or tolerated militancy and the exploitation of anti-American nationalism, Pakistan's deeper embrace of China at the expense of its floundering economy and massive external debt, growing tensions with India, and an unmanageable Afghanistan under the Taliban, Jawid Ahmed and Douglas London claimed in their writings for FP.

While there is no consensus on these issues among Pakistan's various internal forces, any Washington-friendly policy deployed by Pakistan's incoming government could play into Khan's narrative of an American conspiracy. The Army reaps what it sows by having for years played up the false caricature of U.S. intrusion while nurturing violent extremists.

The pre-existing political ties may become a cause of germination of problems to get the bilateral relationship back on track as the destabilizing outcomes will reverberate far and wide. While there is no zero-risk approach to dealing with Pakistan, no U.S. security or economic assistance would mitigate Pakistan's longstanding paranoia about the United States.

The diplomatic relationship between the United States and Pakistan is driven by ad hoc security concerns as the two countries hardly share any strategic or economic interests. "Once the security threats vanish, the relationship returns to a position where they hardly share a common interest that would bind them to cooperate", said a foreign policy expert. (ANI)

Source: WORLD