A Legal Rebuff or a Political Reckoning? The Delhi Court’s National Herald Order and Its Wider Implications

A Delhi court’s refusal to take cognisance of the Enforcement Directorate’s (ED) money-laundering complaint in the National Herald case has triggered a fresh round of legal and political debate. The ruling, delivered by Special Judge Vishal Gogne, is not merely a procedural setback for the agency—it raises foundational questions about the architecture of the Prevention of Money Laundering Act (PMLA), the limits of executive discretion, and the political economy of criminal investigations in India. The judgment’s reasoning, grounded in statutory interpretation, intersects sharply with the political narratives that have surrounded this case for over a decade.

At the heart of the court’s decision lies a simple but decisive legal principle: a money-laundering prosecution cannot proceed without a predicate offence registered through a First Information Report (FIR). The court held that the ED’s complaint was “not maintainable” because it originated from a private complaint filed by Subramanian Swamy, not from an FIR relating to a scheduled offence under the PMLA. This is not a minor technicality; it is the statutory backbone of the PMLA framework. Without a scheduled offence, there can be no proceeds of crime; without proceeds of crime, there can be no laundering.

The ED’s case, as the court noted, arose from Swamy’s private complaint alleging cheating, conspiracy, and misappropriation in the transfer of Associated Journals Limited (AJL) assets to Young Indian. But the absence of an FIR meant that the ED’s entire chain of reasoning lacked the legal foundation required for a money-laundering prosecution. The court therefore declined to take cognisance of the complaint and dismissed it at this stage.

The ruling underscores a recurring tension in PMLA jurisprudence: the ED’s expansive interpretation of its own powers versus the statutory requirement of a predicate offence. The court’s reasoning aligns with earlier judicial observations that the PMLA is not a standalone penal code; it is parasitic on the existence of a scheduled offence. Without that anchor, the ED’s prosecution cannot legally float.

The court also noted that the Delhi Police’s Economic Offences Wing has now registered an FIR in the matter. This development, the judge said, makes it premature to examine the merits of the ED’s allegations at this stage. In other words, the ED may still pursue the case, but only after the statutory prerequisites are satisfied.

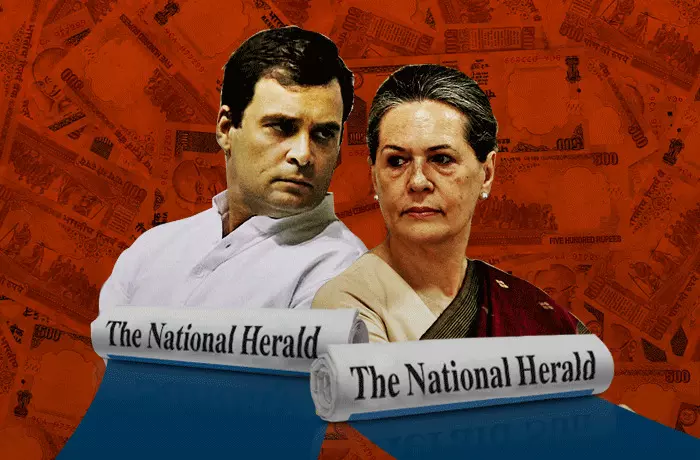

The legal reasoning is clear, but the political context is impossible to ignore. The National Herald case has been a political flashpoint since Swamy first filed his complaint. The ED’s involvement, the timing of summons, and the prolonged nature of the investigation have all been interpreted by the Congress as evidence of political vendetta. Congress spokesperson Supriya Shrinate’s reaction reflects this sentiment: she called the ED’s actions “malafide,” “illegal,” and “politically motivated,” arguing that the court’s ruling exposes the government’s misuse of investigative agencies.

The ED, for its part, has maintained that the case involves the alleged laundering of assets worth over ₹2,000 crore, arising from what it describes as a fraudulent takeover of AJL by Young Indian. The Gandhis have consistently rejected these allegations, arguing that the transaction was a legitimate attempt to make AJL debt-free and that no proceeds of crime were generated, used, or enjoyed as required under the PMLA.

One of the more intriguing aspects of the case is the role of Subramanian Swamy. The court’s order indirectly raises a question that has long circulated in political circles: why did Swamy, despite his allegations, not file an FIR? Instead, the ED initiated its investigation based on his private complaint. The court’s ruling suggests that this procedural choice may have undermined the legal sustainability of the ED’s case at this stage.

The ruling also fits into a broader pattern of judicial scrutiny of ED actions. Courts across the country have, in recent years, questioned the agency’s procedures, the timing of its interventions, and its interpretation of the PMLA. Critics argue that the ED has increasingly become an instrument of political pressure, particularly against opposition leaders. Supporters counter that the agency is finally pursuing long-ignored financial crimes.

The Delhi court’s order does not settle this debate, but it adds a significant data point. It reinforces the principle that investigative zeal cannot override statutory requirements. It also signals that courts will not allow the PMLA to be used without the procedural safeguards that Parliament built into the law.

The court has left the door open for the ED to make further submissions once the FIR-based investigation progresses. This means the case is far from over. The ED may refile its complaint after aligning it with the newly registered FIR. The Delhi Police’s investigation will now become the fulcrum on which the next phase of the case turns.

For the Congress, the ruling is a political victory—one that reinforces its narrative of being unfairly targeted. For the government, it is a procedural setback but not a terminal blow. For the ED, it is a reminder that procedural shortcuts can weaken even the most high-profile investigations.

The Delhi court’s decision is a moment of legal clarity in a case clouded by political contestation. It reaffirms the foundational principle that the rule of law cannot be bent to fit investigative convenience. It also highlights the need for investigative agencies to adhere strictly to statutory frameworks, especially in politically sensitive cases.

Whether this ruling becomes a turning point in the National Herald saga or merely a procedural pause will depend on how the Delhi Police’s FIR-based investigation unfolds. But for now, the judgment stands as a reminder that in a constitutional democracy, legality is not a formality—it is the very substance of justice.