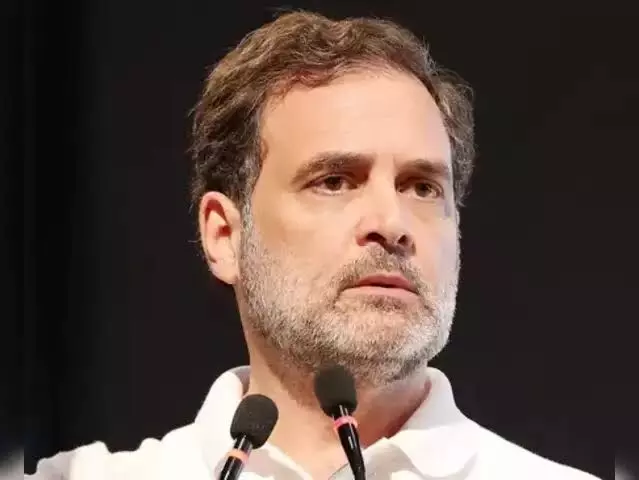

Bihar on the Brink: Rahul Gandhi’s Battle Against the ‘Maharashtra Model’

The politics of India is no stranger to accusations of electoral manipulation, but the recent developments in Bihar have pushed the stakes to a new level. As the state braces for assembly elections later this year, Congress leader Rahul Gandhi has ignited a fierce national debate, accusing the Modi-led NDA government of attempting to import what he calls the "Maharashtra model" of electoral rigging to Bihar. In a protest rally in Patna, Gandhi didn’t hold back—claiming that the elections in Maharashtra in 2024 were rigged in favour of the BJP and warning that the same tactics are being repurposed for Bihar.

At the heart of this controversy is the special intensive revision of the electoral rolls being conducted across Bihar. What would typically be a routine exercise to clean up voter databases has, according to the opposition, turned into a weapon of political control. Gandhi alleges that this revision isn’t about voter verification—it’s about targeted deletion of voters who are unlikely to support the ruling party.

This, he says, is an extension of the same tactics used in Maharashtra, where thousands of names were mysteriously added or clustered under single residential addresses. Investigative findings had pointed to over 1.9 million suspicious or duplicate entries in Maharashtra, but no corrective action was taken. The Election Commission denied wrongdoing, but the opposition maintains that these errors were not coincidental.

In Bihar, a state marked by socio-political complexity, the implications of such a strategy could be even more severe. The Congress and its INDIA bloc allies argue that this revision places a disproportionate burden on the most vulnerable segments of the electorate—especially rural voters, the poor, Dalits, minorities, and youth. Many lack access to documentation or the bureaucratic literacy required to navigate a complex verification process. In effect, this exercise may silently disenfranchise lakhs of voters.

Rahul Gandhi’s speech in Patna, delivered with a red-bound Constitution in hand, reflected both political urgency and moral outrage. He claimed that the Election Commission is no longer functioning as an autonomous body but has become an instrument of the ruling party. Referring to recent changes in the selection process for Election Commissioners—where the Chief Justice of India was removed from the committee and replaced with a cabinet minister—he argued that institutional independence is being systematically dismantled. What was once a consensus-based process is now dominated by the executive, raising concerns about accountability and fairness.

This moment represents more than just electoral rivalry. It is, in the eyes of the opposition, a direct confrontation between two visions of democracy: one rooted in constitutionalism and people’s rights, the other increasingly accused of using state power for partisan gain. Gandhi’s warning, “They want to steal not just your vote, but your future,” was directed especially at Bihar’s youth. With nearly 8 million first-time voters expected in the upcoming election, any manipulation of the rolls would carry outsized consequences. These young voters are seen as crucial to the opposition’s chances, and any artificial reduction in their numbers could significantly tilt the electoral playing field.

Adding force to Gandhi’s protest was the strong presence of allies from across the left and regional spectrum. Tejashwi Yadav of the RJD, D Raja of the CPI, M A Baby of the CPI(M), and Dipankar Bhattacharya of the CPI(ML) all stood beside him, signaling that the INDIA bloc is united in framing the Bihar election not merely as a state contest, but as a test of national democratic integrity. Their combined argument is that voter suppression is being disguised as reform. They point to past data from Bihar where, in previous revisions, hundreds of thousands of names were deleted without proper verification—most commonly from constituencies with large minority and backward-caste populations.

The BJP, for its part, maintains that the revisions are necessary to prevent electoral fraud, particularly from alleged illegal immigrants. But critics argue that these claims are more rhetorical than evidence-based. No official audit or verification has been presented to substantiate the presence of such a large-scale threat. The opposition believes that these narratives are designed to justify politically motivated roll-cleaning—what they describe as "targeted disenfranchisement."

Outside of the electoral technicalities, what’s also being questioned is the public’s declining faith in the institutions that are meant to ensure free and fair elections. A recent Lokniti-CSDS survey indicated that over two-thirds of Bihar’s first-time voters are skeptical about the impartiality of the Election Commission. This growing distrust in democratic institutions may be the most dangerous consequence of the current political climate—because it undermines the very foundation of electoral legitimacy.

Bihar has long been a bellwether for Indian politics, a land where movements for social justice, caste equity, and political resistance have often begun. Rahul Gandhi’s assertion that “This is Bihar—we won’t let it happen here” may sound rhetorical, but it taps into a deeper cultural memory. If the opposition can galvanize this sense of regional pride and democratic vigilance, the coming months could witness a rare fusion of mass politics and electoral consciousness.

Ultimately, the outcome of this struggle over the electoral rolls may not just determine who wins the Bihar assembly elections. It may well shape the future trajectory of India’s democratic institutions. Will the system reaffirm its commitment to fairness, or will it allow itself to drift further into politicized manipulation? That is the real election that has already begun—long before a single vote is cast.