A Rally, a Reckoning, and a Question: Can Democracy Survive When Its Institutions Lose Public Trust

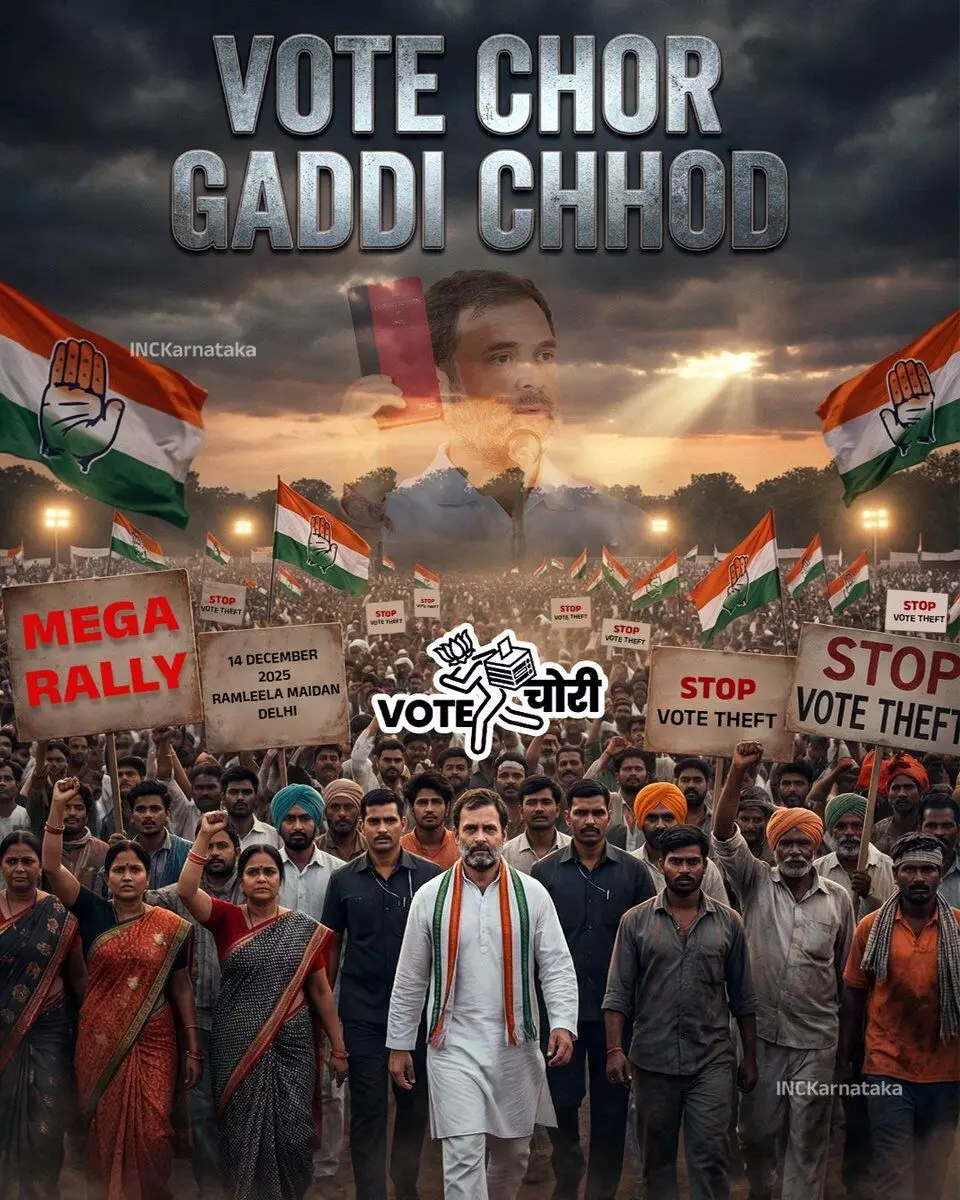

The Congress’ ‘Vote Chor, Gaddi Chod’ rally at Delhi’s Ramlila Maidan marks a moment of unusual political confrontation, not merely between two national parties but between competing claims over the integrity of India’s democratic institutions. The scale of the rally, the sharpness of the speeches, and the direct naming of Election Commissioners by senior Congress leaders indicate a deepening rupture in the political consensus that has historically protected the legitimacy of electoral processes. When a major national party asserts that the Election Commission has become an instrument of the ruling government, the question is no longer about one election or one revision of electoral rolls; it is about the credibility of the democratic architecture itself.

Priyanka Gandhi’s charge that the three Election Commissioners—Gyanesh Kumar, Sukhbir Singh Sandhu, and Vivek Joshi—have “attacked democracy” is a statement that would have been unthinkable in earlier decades. Her insistence that the country “will not forget their names” signals a deliberate political strategy: to personalise institutional accountability and to frame the alleged irregularities in the Special Intensive Revision (SIR) of electoral rolls as a betrayal of constitutional duty. Whether these allegations are substantiated or not, the political effect is unmistakable. A democracy depends not only on the conduct of elections but on the shared belief that the referee is neutral. What happens when that belief collapses? Can electoral legitimacy survive when one of the principal actors in the democratic contest openly declares that the umpire is compromised?

Rahul Gandhi’s framing of the struggle as one between Satya and Satta—truth and power—extends this narrative into a moral register. His claim that the Election Commission “is working with the BJP government” and that the ruling party engaged in financial inducements during elections without facing action is intended to portray the electoral field as fundamentally uneven. The Congress’ argument is not simply that it lost elections, including the recent Bihar Assembly polls, but that it lost them in a system where the rules themselves were manipulated. This raises a deeper question: if opposition parties believe that institutions have ceased to be impartial, what mechanisms remain for democratic correction? Street mobilisation, symbolic protest, and public naming of officials become tools of political resistance, but they also risk further eroding public trust in institutions that cannot easily be rebuilt.

Mallikarjun Kharge’s description of those involved in “vote chori” as gaddars—traitors—adds another layer to the rhetoric. By invoking betrayal of the Constitution, he positions the Congress’ struggle as a defence of constitutional morality against ideological capture by the RSS. This is not merely an electoral argument; it is an ideological one. It suggests that the contest is not between two political parties but between two visions of India. Yet this framing also invites scrutiny. If every electoral defeat is attributed to institutional bias, does it leave any room for introspection within the party? Or does it risk reducing democratic contestation to a perpetual cycle of accusation and counter-accusation?

The BJP’s response, unsurprisingly, seeks to invert the narrative. By accusing the Congress of attacking the Constitution and attempting to “save the family,” the ruling party frames the rally as an act of political desperation rather than democratic defence. The allegation that a Congress leader spoke of violence against the Prime Minister adds a moral charge to the BJP’s counter-attack. But this response, too, raises questions. If the ruling party dismisses all criticism of electoral processes as motivated or anti-constitutional, does it risk appearing intolerant of scrutiny? In a democracy, institutions must not only be impartial; they must be seen to be impartial. The refusal to engage substantively with concerns about the SIR exercise may strengthen the perception that the government is unwilling to allow independent evaluation of electoral mechanisms.

The symbolic protest at the rally—depicting the Chief Election Commissioner in chains—captures the emotional intensity of the moment. Such imagery is designed to provoke, but it also reflects a deeper anxiety: that institutions meant to safeguard democracy may themselves be constrained. Priyanka Gandhi’s allegations that opposition chief ministers were jailed, party bank accounts frozen, and corruption charges selectively deployed reinforce this narrative of institutional pressure. Her metaphor of the BJP’s “washing machine,” where defectors are “cleaned,” is a pointed critique of selective accountability. Yet the question remains: does the repeated invocation of institutional capture risk normalising public cynicism toward all institutions, including those that remain functional and independent?

The Congress’ attempt to link electoral concerns with broader governance failures—rising inflation, unemployment, paper leaks, foreign policy setbacks, and alleged corporate favouritism—reflects a strategic effort to situate the debate within a larger crisis of governance. But this also raises a structural question: can democratic institutions function effectively when political discourse is dominated by allegations of systemic manipulation? If every institutional action is interpreted through the lens of political loyalty, how does a democracy maintain the space for neutral, technocratic decision-making?

The BJP’s counter-argument—that the Congress is using SIR as an excuse to avoid introspection—cannot be dismissed outright. Political parties must confront their organisational weaknesses, electoral miscalculations, and ideological disconnects. But introspection cannot be a substitute for institutional accountability. If there are genuine concerns about the transparency of electoral roll revisions, they must be addressed through open processes, independent audits, and public communication. Dismissing concerns outright only deepens suspicion.

The larger democratic question that emerges from the Ramlila Maidan rally is not whether one party is right and the other wrong. It is whether India’s political actors still share a minimum consensus on the legitimacy of democratic institutions. When that consensus weakens, the democratic process becomes vulnerable not only to manipulation but to delegitimisation. A democracy cannot function when its institutions are trusted only by those who win and distrusted by those who lose. Nor can it function when criticism of institutions is treated as sedition or when institutional accountability is conflated with political attack.

The Congress’ rally is a reminder that electoral legitimacy is not a technical matter; it is a political compact. The BJP’s response is a reminder that political stability requires both accountability and restraint. The real test for Indian democracy lies not in the accusations made at rallies but in the willingness of institutions to demonstrate transparency and the willingness of political actors to uphold the norms that sustain democratic trust.