Karnataka’s “Vote Theft” Scandal: A Shadow Over Democracy in Aland

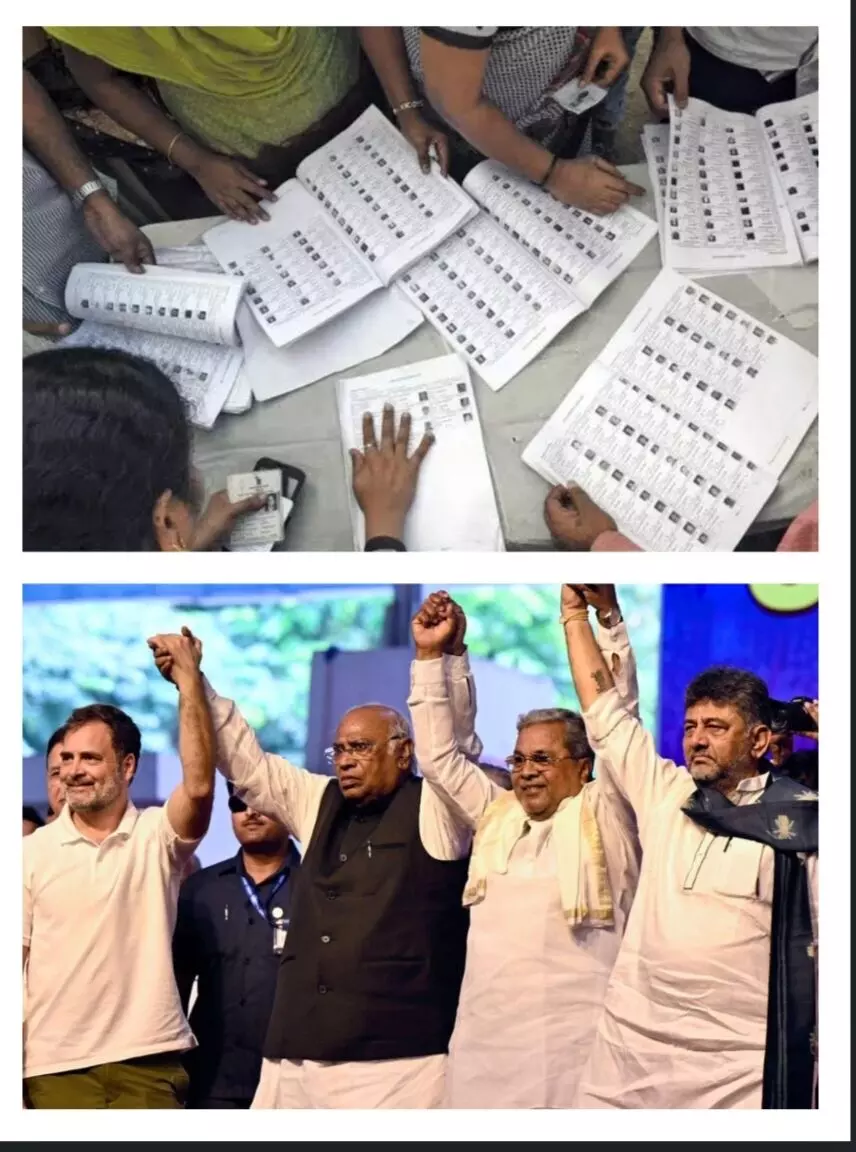

The integrity of India’s electoral process—often hailed as the backbone of its democracy—faces an unsettling question after revelations from Karnataka’s Aland constituency. The Special Investigation Team (SIT), probing what has been described as “vote chori” (vote theft) during the 2023 Assembly elections, has identified six suspects believed to be at the heart of a fraudulent operation to delete thousands of legitimate voters’ names. The scandal, unfolding in the home turf of Congress president Mallikarjun Kharge, has jolted the state’s political landscape and raised concerns about the digital vulnerability of India’s electoral system.

According to official sources in the Criminal Investigation Department (CID), the suspects—linked to a data centre in Kalaburagi—were allegedly paid ₹80 for every deleted vote. Between 6,018 and 6,994 deletion requests were fraudulently submitted through the Election Commission’s online portal. While only a few were genuine, most were targeted attempts to erase the names of Dalit and minority voters believed to be loyal to the Congress party. The operation reportedly relied on the use of Voice-over-Internet Protocol (VoIP) systems to remotely file bogus deletion forms, masking the location and identity of those behind the digital sabotage.

This calculated effort came to light when Congress MLA B. R. Patil of Aland and Minister Priyank Kharge of Chittapur raised the alarm about suspicious deletions. Their complaint to the Chief Electoral Officer (CEO) prompted an immediate halt to the process, averting what could have been a large-scale subversion of voter rights. “Applications were filed to delete 6,994 Congress votes comprising Dalits and minorities,” Patil told PTI. “The deletion was stopped after the CEO intervened. Had this not been caught, I would likely have lost the election.” Patil eventually defeated BJP’s Subhash Guttedar by a narrow margin of 10,000 votes—an outcome that, in hindsight, could have been drastically altered by the deletion scam.

Congress leader Rahul Gandhi, speaking in New Delhi, described the episode as a deliberate attempt to undermine the democratic mandate in Aland. “Names of at least 6,018 voters had been illegally deleted,” he stated, calling the incident “a systematic attack on the people’s right to vote.” Gandhi’s statement resonated across party lines, compelling the Karnataka government to constitute an SIT under Additional Director General of Police B. K. Singh to investigate what now appears to be a well-orchestrated conspiracy.

As part of the probe, SIT officers raided premises linked to BJP leader Subhash Guttedar, his sons Harshananda and Santosh Guttedar, and their chartered accountant. Laptops, mobile phones, and several voter-related documents were seized. In a dramatic twist, investigators discovered burnt voter records near Guttedar’s residence, intensifying suspicion of evidence tampering. Guttedar, however, dismissed the allegations, claiming that “the burning was part of Diwali housekeeping activities” and insisting that there was “no malafide intention.” His defense has done little to quell speculation, with officials privately suggesting that the destruction of documents was an act of panic as the probe tightened around the accused.

A senior CID official disclosed, “We questioned about 30 people, and of them, five to six are strong suspects. Attempts were indeed made in Aland to delete votes, and arrests are likely soon.” The SIT believes the suspects functioned as intermediaries between political handlers and the data operators who executed the deletions through the EC’s digital system. Investigations suggest that the fraudulent requests were processed late at night, using multiple IP addresses routed through VoIP to avoid detection.

The case exposes a critical vulnerability in the digital management of electoral rolls, raising doubts about the security protocols governing voter data. The Election Commission’s online systems, though intended to modernize electoral administration, appear susceptible to manipulation when oversight is weak. Experts have long warned that digital voter management, if not backed by stringent verification and audit trails, can become a tool for disenfranchisement rather than empowerment. The Aland scandal provides a chilling real-world example of such a risk.

Beyond its technical dimensions, the controversy carries heavy political undertones. Aland, being the home turf of Mallikarjun Kharge, holds symbolic weight in Karnataka politics. Any manipulation of its voter rolls would not only have electoral consequences but also strike at the political stature of the Congress president himself. Analysts argue that the episode reflects a growing pattern where elections are increasingly fought not merely on the ground but in data servers and digital platforms, with technology emerging as both a tool of transparency and a weapon of deceit.

The Karnataka government’s decision to form an SIT signifies an acknowledgment of the gravity of the situation. Preliminary findings reportedly confirm that local police and the CID’s cybercrime unit had earlier pointed to discrepancies in voter lists that were “on the dot.” These findings align with suspicions that the deletions were part of a larger organized effort rather than isolated clerical errors. The SIT’s challenge now lies in tracing the financial and digital trails connecting the accused to potential political benefactors.

While the probe continues, the Aland “vote theft” case reignites a larger national debate: how secure is India’s electoral democracy in the digital age? With the increasing reliance on online voter registration and electronic verification, cases like these underscore the need for robust cyber safeguards and institutional vigilance. For a democracy that prides itself on its free and fair elections, even the slightest perception of tampering can erode public trust.

The Aland case is more than just a local scandal—it is a reminder of the fragility of democratic processes when technology, politics, and vested interests collide. If proven true, the systematic deletion of votes based on caste and community affiliation would not only constitute electoral fraud but also an assault on the very principles of equality and representation. The outcome of the SIT’s investigation will, therefore, have implications far beyond Karnataka, setting a precedent for how India confronts digital manipulation in its electoral machinery.

Democracy, after all, rests not just on the right to vote but on the assurance that every vote counts. The revelations from Aland compel both the Election Commission and political parties to introspect: are we safeguarding that right—or silently watching it being deleted, one click at a time?