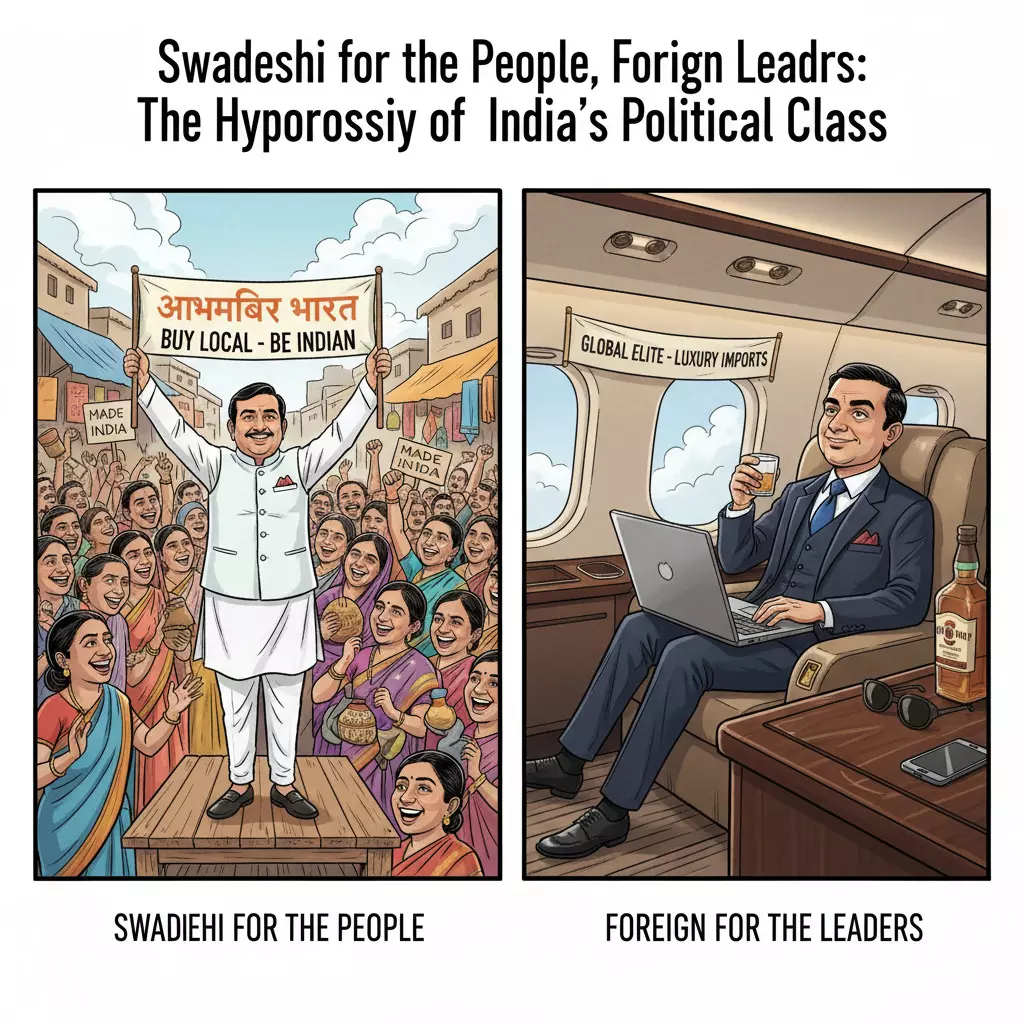

Swadeshi for the People, Foreign for the Leaders: The Hypocrisy of India’s Political Class

When Railway Minister Ashwini Vaishnaw and members of the Union Cabinet champion the call for swadeshi, it is projected as a national mission, almost a moral obligation for ordinary Indians. From the prime minister down to parliamentarians, the message has been consistent: adopt swadeshi products, support Indian industry, and build an economy of self-reliance. Yet, the most glaring contradiction lies not in the slogan itself, but in the lifestyles of those who preach it. A closer look reveals that the very leaders advocating swadeshi are often the least committed to it in practice. From the shoes on their feet to the pens in their pockets, from their mobile phones to the glasses they wear, most of their belongings are manufactured abroad. This dissonance between public rhetoric and private consumption exposes a political culture where symbolism has triumphed over sincerity.

The hypocrisy becomes sharper when one examines the choices made for their own children. A significant majority of ministers, parliamentarians, and political elites have sent their sons and daughters to universities in the United States, the United Kingdom, Australia, or other Western countries. If India’s education system, built and promoted under the same leadership, is supposedly on par with global standards, why is the next generation of the ruling class not studying here? This reality shows that the rhetoric of swadeshi is often reserved for the common voter who survives on subsidised rations and makes do with limited choices, while the elite quietly secure the best of foreign goods and education. Swadeshi, it appears, is for the ruled, while the rulers pursue a cosmopolitan lifestyle without guilt.

The contrast with the independence era could not be starker. When Mahatma Gandhi gave the call for swadeshi, it was not mere posturing. He turned the spinning wheel, the charkha, into a symbol of economic independence, urging Indians to boycott British goods and produce their own. The freedom movement shifted dramatically because millions responded to this call. Ordinary Indians, often at immense personal cost, abandoned foreign cloth and embraced khadi, forcing the colonial rulers to recognise the power of economic resistance. Swadeshi then was not an advertisement; it was a revolution.

Compare this with today’s hollow campaigns. The government routinely invokes Gandhi, yet centres that once trained artisans in spinning and weaving have shut down due to lack of attention. Khadi is paraded during official functions but rarely forms a part of genuine consumption among the ruling elite. Even Lal Bahadur Shastri, India’s former prime minister, had once requested dowry in the form of a charkha, highlighting his commitment to the philosophy. Today, however, swadeshi has been reduced to a slogan in glossy advertisements, a tool for image-building rather than a genuine economic mission.

The economic data too reflects the gap. Despite years of campaigns for Make in India and Atmanirbhar Bharat, India’s imports of electronic goods have risen sharply. According to commerce ministry data, electronic imports crossed $77 billion in 2023–24, with mobile phones and components forming a significant chunk. Even defence procurement, long touted as a sector for indigenisation, still relies heavily on imports—India remained the world’s top arms importer between 2019 and 2023, as per the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. In pharmaceuticals, despite India being termed the “pharmacy of the world,” nearly 70% of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) are imported from China. Clearly, the gap between slogans and ground realities remains wide.

This contradiction between policy and practice weakens the credibility of the swadeshi movement in the modern context. When leaders call upon ordinary citizens to buy Indian, while themselves buying foreign, it reduces swadeshi to an exercise in mass mobilisation without moral conviction. Worse, it creates cynicism among the public, who see through the performance. A genuine swadeshi policy would require leaders to lead by example: wearing khadi not just on Gandhi Jayanti but every day, using Indian products consistently, and enrolling their children in Indian universities to strengthen faith in domestic institutions. Without such personal commitment, swadeshi becomes another political tool—invoked to stir patriotic emotions but discarded when it comes to personal convenience.

The tragedy is that the true potential of swadeshi as an economic philosophy remains untapped. At its core, swadeshi was never about protectionism alone; it was about dignity, self-sufficiency, and collective empowerment. It could still be a powerful tool for local manufacturing, small industries, and farmers—if practised with honesty. But to revive that spirit, the government and political class must abandon hypocrisy and embrace authenticity. Otherwise, swadeshi will remain a story of two Indias: one where the elite enjoy the privileges of foreign goods and education, and another where the masses are lectured on sacrifice.

Until this gap is bridged, the rhetoric of swadeshi will continue to ring hollow. What Gandhi began as a transformative movement for independence has today been reduced to political theatre. India deserves better—policies rooted in action, not advertisements, and leaders who embody what they preach.