When Bihar’s Youth Became “Pieces of the Heart” — The 1967 Political Earthquake

With Bihar preparing for another Assembly election, political leaders are busy unveiling their slogans. Chirag Paswan speaks of “Bihar First, Bihari First,” while Prashant Kishor promises “Bihar on the Path of Change.”

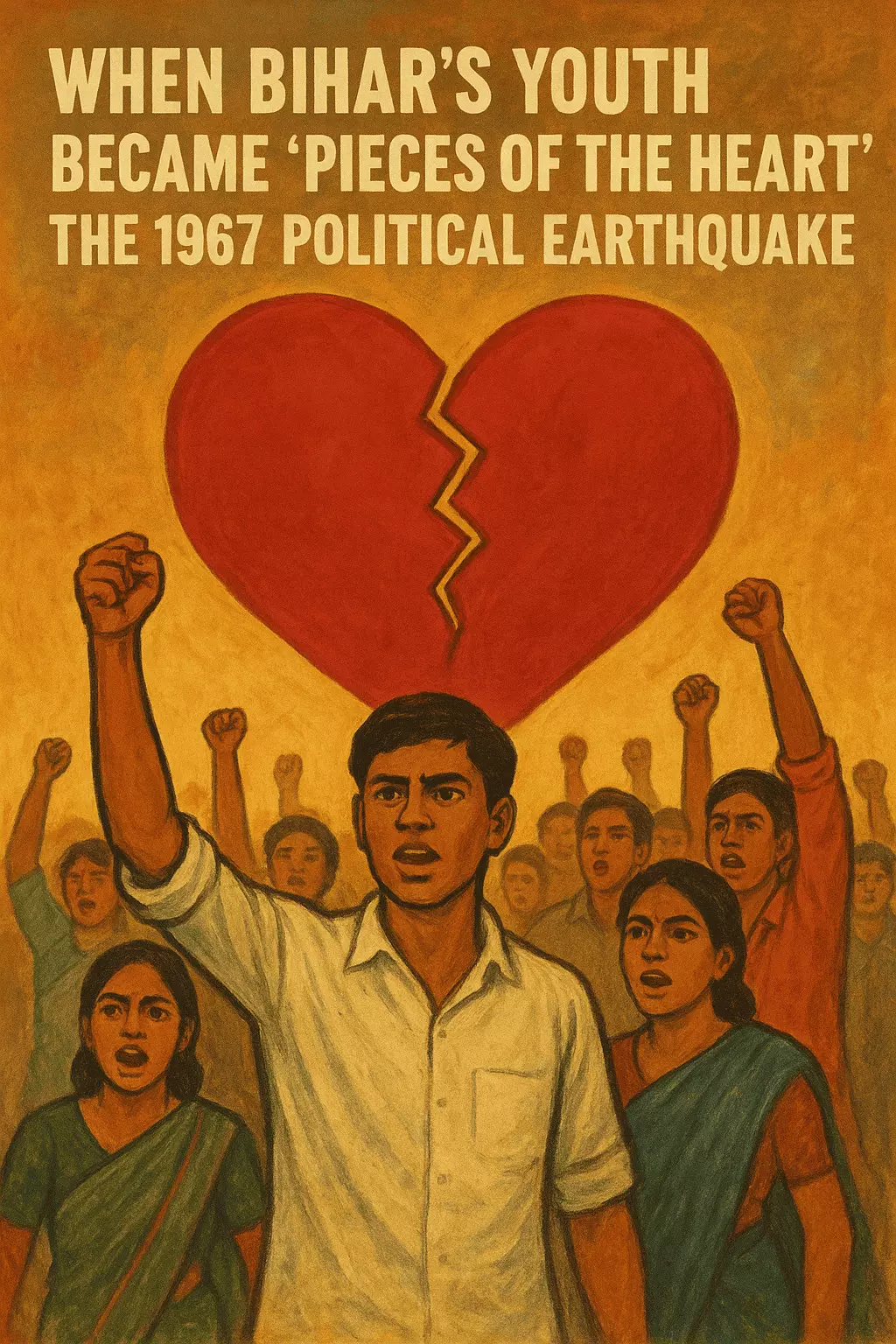

But more than five decades ago, in 1967, one cry resonated across the state like none other. “My beloved children, the pieces of my heart” (मेरे जिगर के टुकड़े). It was not just a slogan — it was an emotional invocation that shook Bihar’s political foundations and gave birth to an experiment in coalition politics.

The man behind the cry was Mahamaya Prasad Sinha, once president of the Bihar Congress Committee. He had broken away from the Congress to form the Jan Kranti Dal, riding on the anger of the youth. The immediate spark was a tragedy: police firing on students at Patna’s B.N. College that killed Dinanath Pandey.

The incident lit the fuse. Students poured into the streets, torching government buildings, chanting slogans against the establishment. Chief Minister Krishna Ballabh Sahay — credited with enforcing zamindari abolition — suddenly found his legacy dwarfed by a wave of resentment.

Against this backdrop, Sinha’s impassioned words struck a chord. At rallies, he would raise his voice to the youth: “When bullets strike my children, how can I remain whole?” At one such electrifying meeting, he even tore his shirt to show his anguish.

Students on Bicycles, Pamphlets in Hand

What followed was unlike any campaign Bihar had seen. Students became the foot soldiers of the Jan Kranti Dal. On bicycles, they roamed through villages and towns, distributing handbills and pamphlets that carried Sinha’s fervent appeal.

In Patna West, the unthinkable happened. The sitting Chief Minister Sahay was defeated by none other than Independent candidate Mahamaya Prasad Sinha — by a margin of seven thousand votes.

Once in power, the government moved swiftly to reward the very group that had carried it to victory. Its first major decision was the radical Pass Without English policy — allowing students who failed in English at the matriculation level to be declared successful.

Bihar also witnessed its first grand coalition, bringing together strange bedfellows: the Jana Sangh, the Communists (both CPI and CPM), the Samyukta Socialist Party, the Praja Socialist Party, and the Swatantra Party. Karpoori Thakur, as Deputy Chief Minister and Education Minister, rolled out concessions for students, including reduced bus fares and even separate cinema counters for them.

Campaigns of Simplicity — and Contrasts

Campaigning then was starkly different from the spectacle of today. Ramawatar Shastri, CPI MP from Patna, went door-to-door in a pedalled rickshaw, addressing meetings in colonies like Chitkohra Bazar, where makeshift podiums were built with wooden cots.

Congress candidate and Education Minister Deena Nath Verma also campaigned on a rickshaw — autos had not yet arrived on the scene. Most prominent candidates, such as Dr. A.K. Sen and Prof. Naramdeshwar Prasad, relied on their students as star campaigners.

Yet, there were exceptions. Kamakhya Narain Singh of the Swatantra Party, remembered as the Maharaja of Ramgarh, campaigned by helicopter. At his sprawling Padma Palace, he even fielded family members, staff, his driver, and cook as candidates in the Assembly elections.

The Legacy

The 1967 Assembly elections marked a turning point in Bihar’s political history. For the first time, students emerged as a decisive force, and coalition politics took firm root in the state. Mahamaya Prasad Sinha’s rallying cry — “My beloved children, the pieces of my heart” — remains etched in memory, a reminder of a time when the youth were not just voters,but the heartbeat of a revolution.